Birmingham truly just kept on giving. After the Back to Backs and the Cadbury Factory and the Balti there were still a couple of sights to squeeze in before hopping the train back to London. Birmingham has no shortage of industrial history and now has many small museums dedicated to the various trades that once thrived in the city. For instance very near my AirBnb was the Pen Museum where I got to cut and stamp my own pen nib and learned that there was a time when “three-quarters of everything written in the world was written with a Birmingham pen.” Impressive indeed.

The Pen Museum probably deserves greater mention, being a lovely, small, volunteer-run sort of outfit that falls into the Plucky Off Beat category and deserves love and support. However, the quirkiness award in Birmingham must surely go to the Coffin Works Museum, the preserved premises of Newman Brothers. From 1894 to 1999, Newman Brothers specialised in the manufacture of brass fittings for coffins - the handles, breastplates, crucifixes, and other ornaments known collectively as coffin furniture. (Similarly, here in the UK the hinges and handles and other bits for doors are called “door furniture” as opposed to “door hardware” in North America. I use the term frequently at work but still find that hard to get used to and often find myself picturing happy families of doors pouring over catalogues of door couches and door ottomans and door dining room tables and such.) Newman Brothers was (and in some ways still is) renowned as one of the finest coffin furniture makers in the world, having supplied the funerals of Winston Churchill, Joseph Chamberlain and many members of the Royal Family, including George V, George VI, the Queen Mother, Princess Margaret, and Diana, Princess of Wales.

Astute Go Stay Work Play Live readers will perhaps have noted that I said the company ceased trading in 1999, whereas the Queen Mum downed her last G&T in March of 2002. Such is the reputation of Newman Brothers coffin furniture that the inventory still in existence (and there is a lot of it) is kept in storage for the right clients. It’s entirely likely that sets of Newman Brothers coffin furniture are currently put aside for still-breathing members of the royal family, ensuring there’s no chance a British Royal coffin will be forced to employ grubby foreign hardware.

The Newman brothers Alfred and Edwin (and one sincerely hopes Alfred’s middle name started with an E) started trading in 1882 as a foundry for brass goods of all kinds at a site in the Eastside area of Birmingham. By 1894 they moved to the location where I found them, at Fleet Street in the Jewellery Quarter very near the canal. At that time they started trading specifically in coffin furniture and also branched out into soft goods - shrouds, robes and coffin liners. Remarkably, the business remained in Newman-run hands until 1952. There followed a period when the business was run by a small group of shareholders, but the most notable part of the company’s management history may be when it was taken over by Joyce Green in 1989. Miss Green started at Newman Brothers as an office secretary in 1949, worked her way up in the company, and finally became the sole owner in 1989. She remained in charge until the vagaries of the global coffin furniture industry finally forced them to close the doors in 1999. By that time Miss Greene not only owned the company outright but also the freehold. (For non-UK readers I really don’t have the energy to get into the whole leasehold/freehold thing. You’ll have to figure it out for yourself. And when you do, please explain it to me.)

However, Miss Green’s involvement with Newman Brothers did not end when the company dissolved. She campaigned to have the building and contents preserved as a museum and by 2000 the factory was given Grade II* listed status. Funding dramas delayed works but major resotration work eventually took place between 2013 and 2014 and the museum opened to the public in October of 2014. The only access to the factory is by pre-booked guided tours, so I was careful to book ahead and presented myself smartly at the appointed hour in the Coffin Works gift shop, where I was presented with an old fashioned timecard and instructed to punch in on the original factory time clock.

The tour was led by a very enthusiastic volunteer who started us out in the courtyard of the building. Newman Brothers coffin furniture was made by two different methods - casting and stamping - which are exactly what they sound like. Casting involved creating the moulds, pouring the cast pieces, tumbling them to remove the sharp egdes, and then polishing them. And here I have to admit that it’s been more than a month since I was in Birmingham and I’ve got an intriguing note from the day that says, “Blacking shop. Green hair” that I don’t really remember anything about. I think it was something to do with the chemicals involved in one of the various nasty industrial processes turning the hair of the workers green. Yes. Let’s go with that. (I’ve also got a note that says "Coffin makers were garage lenders” which must be some kind of autocorrect situation.)

One thing I was careful to remember was about the barrelling shop. (Though not why it’s called the barrelling shop. Let’s say it was because that’s where they tumbled cast pieces in barrels to knock off the flashing). What I did write down properly was a note about how the spinning barrels in the barrelling shop - and the other large power tools in adjacent workshops - were driven by belts looped around a single central axle in the ceiling, which was powered by a gas engine (disappointingly not steam driven). This sort of belt drive system was once very common, allowing a single engine to power machines throughout a whole factory, even over multiple levels. At the beginning of a break or the end of shift rather than powering down the whole system, each tool operator was able to knock the belt for his machine off the drive pulley and onto a slave pulley to take the tool out of service, which is the origin of the phrase “knocking off”. And you’re welcome.

Handles for coffins were usually cast, but the lighter pieces like nameplates and decorative breastplates were stamped from thinner metal. To do that the original design had to be drawn onto a solid block of metal - in mirror image - and then chiselled and sanded by hand into the desired pattern, a process that could take weeks or even months for skilled workers.

Once the design was finished it still needed a mating piece called a “force” for the stamping action to work. The force was cast inside the concave stamp and then with the stamp set carefully under the hammer and the force mounted onto the hammer above, a thin piece of metal could be pressed between the two, creating the finished design. The biggest hammer in the restored stamping room at Newman Brothers was a mighty 30 tons, though it’s no longer operational. The current workshop has a single hammer they still operate for demonstration purposes, which of course requires a lot of prep time, health and safety gear, and imprecations to stand well clear. When the factory was in operation , hammers would strike every two seconds.

Workers at Newman Brothers were paid on a piecework basis with no pension or holiday pay, and they worked six and a half days a week. However, Newman Brothers was a surprisingly enlightened employer in some ways and many of their workers were extremely loyal. Miss Green was not the only employee with an exceeding fondness for the company. Long-time employees could expect a generous lunch party on their retirement, usually held on the premises in the large first floor Assembly Room. Instead of a gold watch, the honouree was encouraged to choose their own retirement gift meaning that many were able to upgrade their living conditions with a new fridge, cooker or carpet. A surprisingly sensible approach, I think. And of course each retiring employee was given their own personal gown and set of coffin handles for future use.

There was also a tea trolley for elevenses, and they played the radio for workers in the shops, an uncommon practise at the time. They even had big Christmas parties on site and a 100th birthday celebration for a particularly loved employee - Miss Dolly. Dolly Dunsby started at Newman Brothers in 1915 at just 14 years old and stayed until her retirement in 1975. Such was the loyalty of Newman Brothers employees that even after the company closed shop in 1999, some of the machine operators would still visit the factory every Friday to oil the machinery and take care of the place.

Though the sewing room branch of the business was never profitable, Newman Brothers maintained it in order to provide a complete service to funeral homes, thus ensuring that the local funeral directors wouldn’t end up taking their trade elsewhere. They were also leaders in other crafty sales techniques. For instance, they were some of the first to create catalogues of their wares with removable pages so they could be updated easily and quickly. And they didn’t print the prices on the catalogue pages - a practice I hate, while still acknowledging its practicality.

The museum website talks some about the restoration of the building and says they elected to recreate the factory in the 1960’s style largely because the company never updated its furniture and fittings beyond that era. This was in evidence in the company office, where Miss Green’s desk is preserved and a Gestetner copier sits idle on a nearby table.

A computer may never have darkened the door of Newman Brothers, but they apparently had the first telephone answering machine in Birmingham. This makes sense, as the funeral business is one that happens at any hour. It was common for funeral directors to call up overnight ordering coffin furniture and for the staff at Newman Brothers to package it in the morning and dispatch it on the city bus that stopped outside the office on Fleet Street.

The tour of the Coffin Works was really excellent, partly because the topic is interesting and the building is well presented, but largely because our guide was so enthusiastic. He’d been part of the team involved in the original purchase of the building from Joyce Green and had stories about visiting the factory to meet with her about the project, most of which seemed to involve the generously stocked drinks cabinet in the office. The tour was schedule to last 90 minutes but stretched well over two hours simply because our guide was so effusive. On contemplating a tour of a factory that dealt so intimately with death you’d expect it would be a somber and morbid experience, but the Coffin Works was bright and happy and full of people who were glad to be there, myself included. So despite the cold and rainy weather outside, I left Newman Brothers with a spring in my step and generally contented with life, though most especially grateful that I've got a good umbrella.

Bins of pen nibs in the Pen Museum

Astute Go Stay Work Play Live readers will perhaps have noted that I said the company ceased trading in 1999, whereas the Queen Mum downed her last G&T in March of 2002. Such is the reputation of Newman Brothers coffin furniture that the inventory still in existence (and there is a lot of it) is kept in storage for the right clients. It’s entirely likely that sets of Newman Brothers coffin furniture are currently put aside for still-breathing members of the royal family, ensuring there’s no chance a British Royal coffin will be forced to employ grubby foreign hardware.

The Coffin Works location on Fleet Street.

However, Miss Green’s involvement with Newman Brothers did not end when the company dissolved. She campaigned to have the building and contents preserved as a museum and by 2000 the factory was given Grade II* listed status. Funding dramas delayed works but major resotration work eventually took place between 2013 and 2014 and the museum opened to the public in October of 2014. The only access to the factory is by pre-booked guided tours, so I was careful to book ahead and presented myself smartly at the appointed hour in the Coffin Works gift shop, where I was presented with an old fashioned timecard and instructed to punch in on the original factory time clock.

One of the other participants punching in.

One thing I was careful to remember was about the barrelling shop. (Though not why it’s called the barrelling shop. Let’s say it was because that’s where they tumbled cast pieces in barrels to knock off the flashing). What I did write down properly was a note about how the spinning barrels in the barrelling shop - and the other large power tools in adjacent workshops - were driven by belts looped around a single central axle in the ceiling, which was powered by a gas engine (disappointingly not steam driven). This sort of belt drive system was once very common, allowing a single engine to power machines throughout a whole factory, even over multiple levels. At the beginning of a break or the end of shift rather than powering down the whole system, each tool operator was able to knock the belt for his machine off the drive pulley and onto a slave pulley to take the tool out of service, which is the origin of the phrase “knocking off”. And you’re welcome.

Handles for coffins were usually cast, but the lighter pieces like nameplates and decorative breastplates were stamped from thinner metal. To do that the original design had to be drawn onto a solid block of metal - in mirror image - and then chiselled and sanded by hand into the desired pattern, a process that could take weeks or even months for skilled workers.

Some of these stamps are a foot across, so you can see why it would take a while.

They also ran benchtop presses like this one for small pieces. Called a fly press, they were often operated by women because they’re usually shorter and hence less likely to get whacked in the head by the action of the rotating arm and counterweight swinging around at the top of the machine. (I suspect given the size of the iron ball at the end of the arm that this was a mistake you’d only make once. Though I’d like to think that if they took you out of Newman Brothers in a box, at least it would be one with very handsome handles.)

The Assembly Room, where most of the stock was kept.

These boxes have been left stacked as they were when the company closed.

Each one is still full.

Each one is still full.

We also got a look at the second floor sewing room, where they made gowns, shrouds and coffin liners. This part of the operation was shut down during the war years so that the cloth could be diverted to the war effort. It didn’t start up again until the end of rationing.

The tea station in the sewing room, complete with a list of how each machinist took her tea.

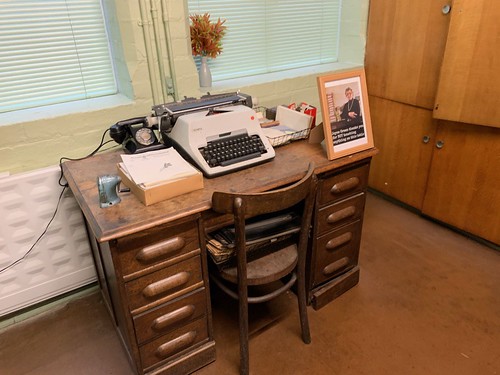

The museum website talks some about the restoration of the building and says they elected to recreate the factory in the 1960’s style largely because the company never updated its furniture and fittings beyond that era. This was in evidence in the company office, where Miss Green’s desk is preserved and a Gestetner copier sits idle on a nearby table.

Miss Green's desk.

The tour of the Coffin Works was really excellent, partly because the topic is interesting and the building is well presented, but largely because our guide was so enthusiastic. He’d been part of the team involved in the original purchase of the building from Joyce Green and had stories about visiting the factory to meet with her about the project, most of which seemed to involve the generously stocked drinks cabinet in the office. The tour was schedule to last 90 minutes but stretched well over two hours simply because our guide was so effusive. On contemplating a tour of a factory that dealt so intimately with death you’d expect it would be a somber and morbid experience, but the Coffin Works was bright and happy and full of people who were glad to be there, myself included. So despite the cold and rainy weather outside, I left Newman Brothers with a spring in my step and generally contented with life, though most especially grateful that I've got a good umbrella.

2 Comments:

This was a treat, Pam.............

Thanks,

Anne Stephenson

Very cool. I do wish there was more info on the pen museum, though...

Post a Comment