I recently got to spend a cold but sunny Sunday on a little jaunt that absolutely perfectly occupied the sweet spot in the Venn diagram of “Quirky London Sites” and “Things that interest Pam” and “Things that are bloggable” - a visit to the Kirkaldy Testing Museum.

David Kirkaldy was a Scottish-born engineer who pioneered the science and practice of methodical materials testing by establishing the first ever independent testing works to determine the strength of the new materials available to Victorian engineers - mostly cast and wrought iron. This was incredibly important because iron as a construction material is part of what fuelled the Industrial Revolution (along with mechanisation, steam power, and a ready supply shoeless orphans to dart around in all the shiny new mangling devices.)

Kirkaldy’s testing works opened in 1866 in a location close to the current site in Southwark. The engineer then later designed his giant hydraulic “Universal Testing Machine" for evaluating different materials in tension or compression, had it built in Leeds, and installed it in a new purpose-built building where it’s still located today. (Mercifully, it’s very much built into the Grade 2 listed property so it would have been difficult to remove anyway. Plus it’s more than 47 feet long, so it’s not like a vandal could have just slipped it into his pocket.) The testing works opened on January 1, 1874 and ran for close to a hundred years, headed by two more generations of Kirkaldy engineers, David’s son and grandson. And along with routine testing of the countless links and bars and columns and beams that built the modern world, Kirkaldy conducted forensic testing on failed structural elements, such as those from the infamous Tay Bridge Disaster. He also continued developing new machines and techniques for analysing materials, and the works received test specimens from around the world.

Luckily, after the works closed the site was recognised by members of the Greater London Industrial Archeological Society, who helped get it listed for preservation. (And can I just say that discovering the existence of the Greater London Industrial Archeological Society was one of the best things about my day? How can they have escaped my detection for so long?) Thanks in part to their intervention, Kirkaldy's works have been a museum since 1983, and it's now open to the public on the first Sunday of every month, staffed with volunteers (much like the poor Kew Museum of Water and Steam which Astute Go Stay Work Play Live Readers will doubtless remember). A visit costs a mere £5 and for that you get a guided tour of the museum’s collection of vintage testing machines and - more excitingly - a live demonstration of some of them.

My guide was a small boiler-suited and bespectacled man who first showed us an introductory video in the basement of the building, and then a few of the smaller machines they keep.

They also have an impressive collection of small moulds for making concrete test pieces, which are shaped like dog bones and used for testing the tensile strength of concrete by pulling the dogbones apart. They’re shaped like dogbones so that the machine has something to grab and so that the bit you grab is larger that the bit you’re testing, so you can be reasonably confident that the test pice will break in the right place and the results will be properly consistent.

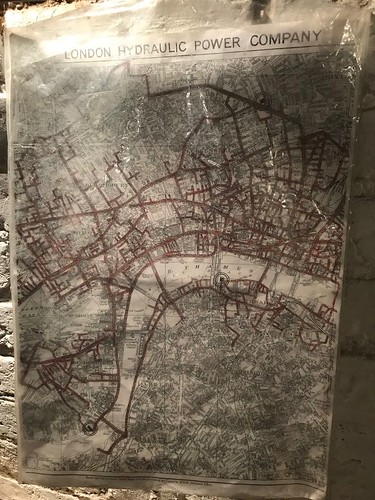

Along with the surprising discovery of the Greater London Industrial Archeological Society, I learned another amazing thing at the Kirkaldy Testing Museum. As recently as 1977, an organisation called the London Hydraulic Power Company supplied high pressure water for hydraulic powered devices to businesses all over London, on both sides of the Thames, through a network of more than 150 miles of cast iron and steel pipes. Before it was established in the late 19th century, companies that wanted to power machinery hydraulically had to run and maintain their own boilers, often also needing to employ large accumulator towers for storing the energy they produced. With the establishment of the London Hydraulic Power Company, pipes ranging in diameter from 2” to 10” eventually stretched from Kensington to the Docklands, powering cranes, lifts, presses and other machinery of all kinds including, of course, Kirkaldy's large testing machine. At Kirkaldy’s they also employed a hydraulic intensifier to take the operating pressure up to an impressive 4,500 PSI.

After viewing the impact tester, and the dogbone puller and a few other things like a 40’ long chain testing machine, we got to move upstairs and actually use one of the smaller devices to pull apart a piece of the devilish reinforced plastic strapping that gets wrapped around heavy pallets or packages and secured with those funny metal clips.

Of course the main reason to visit Kirkaldy’s Testing Museum is to see the big machine in action, which you can do if you stick around until 2pm on an open Sunday. (Or, happily, if you take in the other displays and then decamp to a nearby coffeeshop for a caffeine hit and a nice pain au chocolate and then return at 2pm.) I stationed myself with a good view of the area and watched while the grey-haired volunteers prepared the machine to rip apart a rusty steel bar cut out of an old street grate reclaimed from outside the building.

The hydraulics in the machine only work in one direction, meaning that the hydraulic ram has to be returned to its starting position by heavy counterweight in the basement. Switching the machine from pulling mode (tension) to crushing mode (compression) is quite labour intensive, so we only saw pulling mode. Also crushing mode tends to produce flying debris that is not conducive to public participation.

Once the carriage was in position another volunteer climbed into the machine to set the tiny steel bar into place. As I mentioned before, test pieces are normally shaped to give something for the clamps to grab, but in this case the bar was simply wedged with a series of tapered steel pieces banged in with a large sledgehammer. Nearby displayed showed lots of different wedges used for this purpose.

At the other end of the machine there's a large horizontal arm connected to the measuring part of the device, which consists of a balance arm and a series of counterweights. As the cylinder moves, the arm swings and transmits movement to the balance. The machine operator then slowly winds a gear that moves a counterbalancing weight to keep the big balance arm level, which simultaneously moves a pointer along a marked scale showing the pressure the machine is exerting. Once the sample breaks, the indicated measure can be noted. Or, if the sample is being proof tested, the pressure in the machine can be increased to that proof load to test that the material is adequate. Two out of every fifty of the giant links that make up the suspension chains in the Hammersmith Bridge were tested this way by that very machine.

Our little test piece was about half an inch thick and two inches wide. And though it was impossible to perceive the movement of the cylinder as the test proceeded, there came a point when little flakes of old paint and rust began to fall off the test piece onto a sheet of clean white paper underneath. The volunteer running test then said, “We’re inconveniencing the material” which I thought was a masterfully understated way of putting it, considering that a machine capable of exerting loads up to one million pounds of pressure was, at that moment, attempting to rip apart the chemical bonds inside that poor little piece of metal.

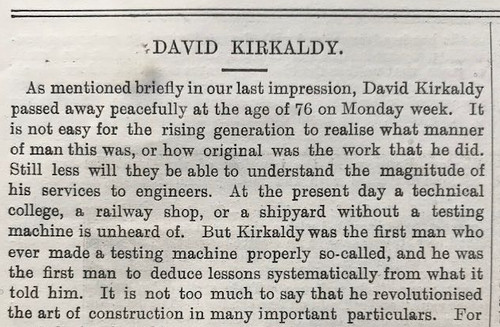

It’s also possible to tour a part of the testing works office, which was quite lovely. There was a large glass fronted wooden bookcase absolutely filled with proper engineering books with titles like The Mechanical Testing of Metals and Alloys, Hydraulic Power Engineering, History of Strengths of Materials, and that classic page-turner, Theory of Elastic Stability. There were also framed copies of Kipling’s Hymn of Breaking Strain and a large framed copy of David Kirkaldy's obituary, published in The Engineer on February 5, 1867.

It’s really not over-egging things, this obituary. David Kirkaldy made a remarkable and unique contribution to the modern built environment. He was methodical, meticulous and, above all, scrupulously honest. To run a completely independent and unbiased testing works, free from outside influence, was absolutely vital to the safe development of all kinds of structures, which of course qualifies him for the Go Stay Work Play Live Hall of Heroes, where he takes up a position alongside Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Joseph Bazagettte, Harry Beck, Captain Picard, and whatever genius it was who invented sticky toffee pudding.

Hidden in plain site on Southwark Street, just a block from the Tate Modern.

The pediment above the former main entrance to the testing works.

Luckily, after the works closed the site was recognised by members of the Greater London Industrial Archeological Society, who helped get it listed for preservation. (And can I just say that discovering the existence of the Greater London Industrial Archeological Society was one of the best things about my day? How can they have escaped my detection for so long?) Thanks in part to their intervention, Kirkaldy's works have been a museum since 1983, and it's now open to the public on the first Sunday of every month, staffed with volunteers (much like the poor Kew Museum of Water and Steam which Astute Go Stay Work Play Live Readers will doubtless remember). A visit costs a mere £5 and for that you get a guided tour of the museum’s collection of vintage testing machines and - more excitingly - a live demonstration of some of them.

My guide was a small boiler-suited and bespectacled man who first showed us an introductory video in the basement of the building, and then a few of the smaller machines they keep.

Like these pendulum impact testing machines, which, as any fool can see, are scientifically designed devices for whacking things in a very precise manner and measuring how much energy they absorb when they break.

This machine slowly adds lead shot to one side of a set of balances, while the other side pulls on the dogbone. When the sample piece breaks, the flow of shot is cut off and then weighed to determine the breaking point of the concrete.

They also make plain cubes for testing concrete's resistance to compression. Of course concrete is massively stronger in compression than in tension, which is why steel reinforcing is added to most modern concrete structures to increase their tensile strength.

"Hydraulic power raised the curtain at the Royal Opera House, rotated the turntable at the Coliseum, raised lifts at the Bank of England (and thousands of other offices and flats) and opened dock gates on the Thames. In its heyday the company's hundreds of workers pushed out up to 30 million gallons a week at 850 pounds per square inch from its six pumping stations.” From Subterranea BritannicaOnce electric motors became established as a means of powering machinery, the need for the system waned and it was eventually closed down completely in 1977. However, a clever group acquired the assets of the company in 1981, recognising the value of the vast system of pipes. Those same conduits are now used to run fibre-optic cables through the heart of London. And I just think that whole thing is fucking fantastic.

A map of the LHPC network unceremoniously displayed in the basement of Kirkaldy’s

The tension mounts. Literally.

There was even one woman on the crew, which is very unusual in my experience. Here she is setting the moving end of the machine to the right position to accept the steel bar.

Once the carriage was in position another volunteer climbed into the machine to set the tiny steel bar into place. As I mentioned before, test pieces are normally shaped to give something for the clamps to grab, but in this case the bar was simply wedged with a series of tapered steel pieces banged in with a large sledgehammer. Nearby displayed showed lots of different wedges used for this purpose.

At the other end of the machine there's a large horizontal arm connected to the measuring part of the device, which consists of a balance arm and a series of counterweights. As the cylinder moves, the arm swings and transmits movement to the balance. The machine operator then slowly winds a gear that moves a counterbalancing weight to keep the big balance arm level, which simultaneously moves a pointer along a marked scale showing the pressure the machine is exerting. Once the sample breaks, the indicated measure can be noted. Or, if the sample is being proof tested, the pressure in the machine can be increased to that proof load to test that the material is adequate. Two out of every fifty of the giant links that make up the suspension chains in the Hammersmith Bridge were tested this way by that very machine.

Here’s the day’s operator gesticulating near the controls for the balance arm.

Eventually the piece broke, after yielding about two inches. Disappointingly the break occurred inside the clamping jaws, so there was no big aha! moment. They did, however, manage to get the pieces out of the clamps, and passed them around.

This is just the first paragraph, but it's appropriately laudatory.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment