It's a two-for-one deal today, on the theme of Charitable Institutions for Poor Children in Victorian London (I can already hear the cheers, "At last!"). Both these small museums came to my attention courtesy of my friend Duncan, who you may remember from previous posts about Chislehurst Caves. Duncan divides his time between Winnipeg and a rather smart little flat in Covent Garden, where he conducts research for upcoming novels. (Disappointingly, the division between Winnipeg and Covent Garden is rather lopsidedly in favour of Winnipeg, but nonetheless I think he'd appreciate being described in such a fashion.)

First up: the Foundling Museum. "Foundling" is a mostly archaic and highly evocative word for a child abandoned by his or her mother, and the Foundling Hospital was an institution set up in 1741 to take in such children, care for them, and educate them. (The word hospital is here used in the outdated sense of being a place that offers hospitality, as opposed to a place for medical care.) Founded by philanthropic sea captain Thomas Coram, the hospital was in use from the 18th century until as late as the 1950s, with thousands of children passing through it. (Incidentally, there's still a foundation for the care of children called "Coram". Among many other good works, they own a large outdoor park and playground that no adult is allowed to enter unless accompanied by a child.)

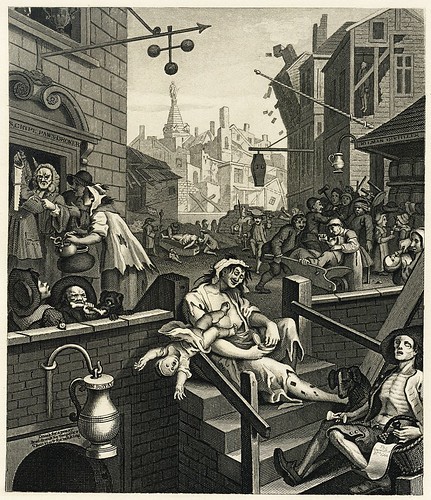

The Foundling Hospital was begun at the height of the Gin Craze in London, a period in the early and mid 18th century when, according to a display in the museum, one in five houses in London was a gin shop. (Stop and think about that for a second. ONE IN FIVE.) The Gin Craze deserves its own post, really. (Indeed, gin has its own sort of museum here.) For now, suffice it to say there was an epidemic of public drunkenness, along with a whole lot of the sorts of activities that tend to go along with there being loads of desperate and incapacitated people hanging around: crime and prostitution. Many liken the Gin Craze and the public backlash against it to the 20th century's war on drugs, especially crack.

Naturally, and heartbreakingly, there ended up being a lot of abandoned children during this time, leading to creation of the Foundling Hospital by the kind-hearted and civic-minded Captain Coram. In the beginning children - generally only babies under one year old - were admitted without question, though admission requirements changed periodically. At times when demand exceeded capacity a mother might have to take part in a lottery to see if her child would be accepted. Drawing a white ball meant the child was in (pending a medical examination). A red ball put the child on a waiting list, and a black ball meant the mother and child were turned away. At other times any child offered up was accepted, though this led to terrible mortality rates due to overcrowding and the prevalence of disease among the unscreened children.

Once accepted, babies were sent to wet nurses in the countryside where they stayed until they were four or five years old. Many reported this as being a very happy time in their lives, though some were ill-treated by their foster families and mortality rates were high. If the child survived, they returned to the hospital where they lived and were schooled until they were old enough for boys to be apprenticed or enlisted in the military, and for girls to enter service as housemaids. Being admitted to the hospital may have been far superior to being abandoned on the street, but don't imagine that life was all Little Orphan Annie for the foundlings. Certainly they were better off than if they'd been left on the streets, but mortality rates were still shockingly high. The museum displayed a register of children who'd been admitted, listing their names, date of admittance, and eventual fate. The page shown had six to eight names, and only two were listed as anything other than "deceased".

Sometimes the mother would leave a token to identify the child so that she could come back to claim it if her circumstances changed. Later, written records like the ones I mentioned were kept and a mother would have to pay large (non-refundable) fee just to find out if her child was still alive. In the not-at-all-certain event that the child was still living, further fees applied for it to be released back to the mother. Unsurprisingly, this was exceedingly rare.

Sometimes the mother would leave a token to identify the child so that she could come back to claim it if her circumstances changed. Later, written records like the ones I mentioned were kept and a mother would have to pay large (non-refundable) fee just to find out if her child was still alive. In the not-at-all-certain event that the child was still living, further fees applied for it to be released back to the mother. Unsurprisingly, this was exceedingly rare.

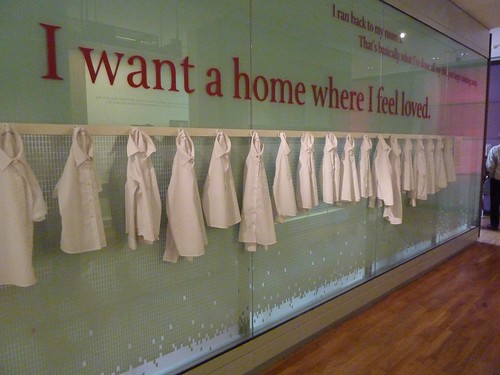

Life for the foundlings at the schools was harsh, but actually quite forward-thinking for the time. The kids all wore uniforms, rose early, washed in cold water, and ate quite a progressive diet, including having meat many days. Their education also included study of music, for reasons which will shortly become apparent. Medical care at the school was also quite advanced, with an emphasis on cleanliness and fresh air in medical wards. And small pox innocuations at the school are recorded as early as 1744, which is frankly astonishing.

Sadly, "feeling loved" may have been a bridge too far for most foundlings. While their physical needs were met, it was a stern and disciplined place to grow up. No hugs.

All of this progressive care cost money of course, and where the money came from is the other part of the story of the Foundling Hospital. Thomas Coram was aided in funding the hospital by the patronage of two well-known artists of the time, the composer George Frideric Handel, and the painter William Hogarth (he of the "Gin Craze" etching above). Handel often performed "Messiah" at the institution, and was a governor of the school, where music became an important part of the curriculum. Hogarth and his wife were also patrons; they fostered children themselves and Hogarth donated several canvases to the school. Other artists also donated to the hospital, which amassed an impressive collection as a result, becoming, in effect, the country's first art gallery open to the public. Much of the Foundling Museum is now dedicated to displaying the collection, and the top floor also houses a display related to Handel, including Handel's Last Will and Testament and a complete score for "Messiah" that he bequeathed to the hospital in it. The hospital also benefitted from the Victorian penchant for Good Works of all kinds, and this, along with the patronage of popular artists like Hogarth and Handel, made the Foundling Hospital a fashionable cause, ensuring funding for its continued existence.

The Foundling Museum was a bit unexpected. I'd been hoping for a lot more information about the hospital itself - the children, their life, the conditions at the time - and fewer rooms dedicated to big oil paintings. Instead, that interesting (to me) part of the museum was contained in just one room, with the rest of the building dedicated to the impressive collection of art and sculpture that I guiltlessly skipped over (though I did go have a peek at Handel's Will). Happily though, this left me plenty of time to make my way out to the East End to the day's second location: The Ragged School Museum.

Ragged Schools were set up in poor areas of London to provide free education and hot meals for children in the 19th century, hence the name; the student were, quite literally, ragged. By 1867 more than 200 day schools were established, along with a similar number of evening schools (generally for adults) and Sunday schools. It's estimated that more than 300,000 children went through London's Ragged Schools in a forty year period in the mid to late 19th century. (The schools were eventually closed when local authorities took over education in 1902.) The Ragged School Museum is set up on the site of a Ragged School founded by the well known philanthropist Dr. Thomas Barnardo. (Barnardo's is now the UK's leading children's charity which, among other things, runs a decent charity shop in Brixton.) The museum is housed in an old industrial warehouse alongside the Regent's Canal, which is a pleasant walk from Mile End tube station, especially if one has just had a nice lunch and a good cup of coffee and the sun is shining.

The museum is mainly geared to school children, 14,000 of whom visit each year to get a taste of what life was like for poor Victorian kids. There's a classroom on an upper floor, equipped with real old desks and accoutrements, and visiting kids dress up in ragged clothes and draw on slates and have an hour long lesson taught by an actress in Victorian dress. There was a class of kids there when I visited, and I could hear them reciting back what the teacher was saying. She was trying to teach them the old pre-decimal pounds-shillings-pence system, which is hard going if you ask me, especially with farthings ha'pennys and bobs and guineas and crowns thrown in. Still, it looked like a great day out.

Here's me in the classroom, contemplating how many silver sickles to a rouble or furlongs to a firkin or something like that.

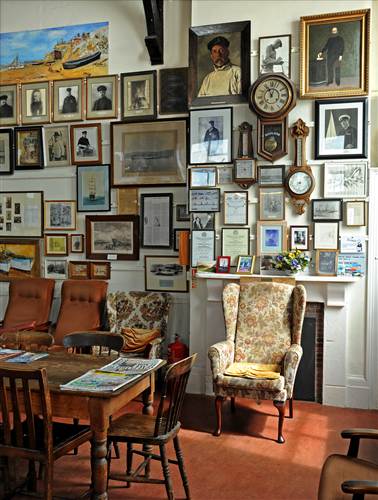

The floor above the classroom has a few small displays, again mainly geared to kids. The building itself is nicely restored and just a pleasant place to be. You can see the big windows that overlook the canal, and wide planked wooden floors, and it has a charmingly worn-but-scrubbed feeling and a clever two-tone paint scheme. Apparently, the chocolate brown colour on the lower half of the walls was Barnardo's idea and was designed to hide the marks left by small grubby hands. There's also a large room of displays about the surrounding East End neighbourhoods on the ground floor, and even a small gift shop.

I lingered at the Ragged School. While the Foundling Museum was definitely more polished and must be better funded (judging by the £7.50 admission fee), the Ragged School Museum is a bit rough around the edges (and free!). You could tell that it's operating on a bit of a shoestring, and I sense that a lot of the people involved are volunteers (though their website does have a "Jobs" section, so someone must get paid for something). The museum itself came about when the building was threatened with demolition in the 1980s and local residents joined together to save it. And the guy at the front desk had the enthusiasm you usually only get see from volunteers; he chatted with me at length about the school, the building, and the surrounding neighbourhood. I really liked the place. Certainly, it seems to have an appropriately East End vibe, whereas the Foundling Museum felt very much like a place that still relies on wealthy patrons. I suppose in that way both places really are simply refections of their pasts.

And with that tiny and unexpected bit of insight, I'm off again for another week.

And with that tiny and unexpected bit of insight, I'm off again for another week.