In general English usage a barbican (note the indefinite article and lack of capital B) is the defensive bit above the gatehouse of a castle or walled city. In general London usage, the Barbican (with definite article and capital B) is a massive and mostly impenetrable concrete complex comprising 38 acres of residential apartments, cinemas, restaurants, schools, galleries, theatres, gardens, lakes, fountains, and parking garages, along with two concert halls, assorted shops, a museum, a library, a church, two tube stations, a conservatory, a school of music and drama, two kindergartens, a pub (of course) and, at almost any hour, an uncountable number of people fruitlessly trying to find their way to or from one of the above.

The Barbican is located in the City of London. Again, capital letters play an important role here, differentiating the City of London (note the capital C) - the independent county comprising the square mile of central London most famously home to the UK’s financial and banking sector - from the city of London (no capital C) - which is the metropolis of Greater London and completely surrounds the City of London. (I think we’ve been through this before, so surely any Astute Go Stay Work Play Reader understands this distinction by now.) The area of the City is roughly analogous to the old Roman walled city. The Barbican itself sits just to the north and west of the old Roman city, but bits of the Roman wall are actually still visible on the estate.

For the first half of the 20th century the area where the Barbican now sits was mostly warehouses and other industrial sites. Then during a single night of bombing on December 29, 1940, the Luftwaffe levelled the whole neighbourhood - an area of 35 acres. For the subsequent two decades that patch of London was essentially abandoned and turned into an overgrown (and presumably rubble-strewn, slightly dangerous and very fun) playground for the local children. Health and Safety was, one presumes, not A Thing. Considering the price of real estate in London now it seems astonishing that much land was simply left empty for so long, but I suppose there was a lot of recovery to do in all sectors after the war. Still… twenty years?

When they eventually managed to formulate a plan for using the space the goal was not simply to cram it with as much housing and commercial space as possible. In fact, the aim was much loftier than that. The Barbican was meant to be a physical symbol of how London could rise again after the destruction of the war - a grand showpiece and a bold statement. The architects - Chamberlin, Powell and Bon - set out their intention to create a complete machine for living, with residents able to enjoy modern conveniences, green spaces, and services like libraries, shops, theatres and cinemas, all in a densely developed but also open, inviting highly designed ecosystem combining residential and civic functions with modern design.

Part of that modern design is the architectural style of the Barbican - it’s one of the most prominent examples of Brutalism in the UK, being constructed almost entirely from brick and concrete with exposed aggregate. Interestingly, one might assume the exposed concrete seen all over the Barbican is the actual structural material, but it’s actually a layer added after construction, dried for 21 days, and then pick-hammered by Italian stone masons to create the distinctive texture.

Luckily, one of the Barbican’s 4,000 residents is also one of GSWPL’s more astute readers, and on hearing of my interest in the estate as a whole he extended an invitation for lunch and a private tour with a couple other friends one Sunday in rainy December. This was especially excellent because it meant not just a lovely lunch, but a visit inside a real Barbican flat, and a tour around the estate led by a highly knowledgeable guide in possession of the all-important resident’s key, allowing access to all kinds of places mere plebeian mortals could not presume to tread. The invitation also came accompanied by a painstakingly detailed set of directions for getting from the tube station to the exact location of the flat - no small feat in a complex that is renowned for being murderously difficult to navigate. I’m happy to report I was able to find my way with only one small back-track required.

Did you notice that all of the window coverings in Andrewes House are white on the outward facing side? That’s not a coincidence, it’s actually a condition of residency. You’re also required to cultivate your window boxes if you’ve got them. And don’t even think about removing the carpet and installing wood floors. That’s not allowed, partly to reduce noise transmission between floors, but also partly because heating is provided by in-built electric underfloor heating can get hot enough to burn if not insulated by that layer of carpet. And don’t assume you can simply turn down the thermostat to compensate - the underfloor heating is centrally controlled to turn on overnight when electricity is cheap, meaning while it might be toasty in the morning, it can be downright chilly when you get home from work in the evening.

There are other modern conveniences in the flats that we'd take for granted right now but were, at the time, quite unusual. For instance the kitchens are open to the living and dining area and were designed by marine galley engineers to maximise what was considered to be very little space. Bathrooms featured showers - also not common for the time. Balconies are also included, with a lot of flats having one at each end, a real luxury even today. And many of the Barbican's flats are housed in giant tower blocks, once the tallest residential buildings in Europe. However, these unusual modern touches, coupled with the estate's location in the middle of a bombed out neighbourhood meant that getting people to move to the Barbican was hard work. Difficult to believe from our perspective in 2018, when a 440 square foot studio flat in one of the estate's terrace blocks goes for more than half a million quid.

The all concrete construction makes for a very solid structure but comes with some disadvantages. I knew an architect who was a big fan of Brutalism (architects are often the only champions of this style). One of the reasons he gave for his fondness is that, for an architect, it's a real challenge. When you're pouring concrete that's both the structure and the outer finish of the building, there's nowhere to hide if something goes wrong. There's no covering mistakes behind a layer of plasterboard. Everything has to be designed in from the beginning, including the wiring, so even something as (relatively) minor as a light fixture or a plug socket has the be included at the earliest stage. In the case of the Barbican this means that all the wiring and plumbing is literally set in stone. It can't be changed, and if it was installed incorrectly or breaks, there's really nothing to be done. And forget getting fibre broadband or smart electric or water meters or extra power to anywhere.

If this all seems a bit Big Brother, consider the many advantages of living in the Barbican. For instance, you’ve got London's second largest conservatory on your doorstep. (It was designed to enclose and disguise the fly tower of the theatre!) It used to be open every day, but sadly it’s now just on “selected Sundays and Bank Holidays”.

Another perquisite? Garbage collection happens every weekday. And you don’t have to schlepp your leaky rubbish bags to some sort of central depot. Each flat has a small closet near the front door with a communicating door on the outside, allowing rubbish collectors to come and collect every day without disturbing you. Post arrives in the same way, but in reverse. The estate also has a scattering of sites to take recycling and food waste, and places to handle used electronics.

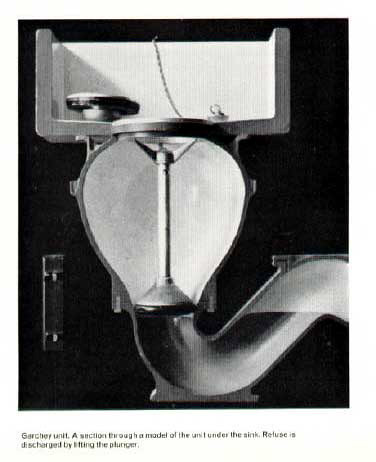

And on the topic of waste collection, surely one of the most interesting quirks of the Barbican must be the infamous Garchey disposal system. Intended to eliminate those rubbish collections I mentioned, the Garchey is like a super-charged in-sink garbage disposal designed not just for wet garbage like potato peelings and coffee grounds but almost everything else except really large and bulky things. Even cans and bottles are fair game (keep in mind this was pre-recycling). With a Garchey system all that waste is put down the sink drain where it sits in a holding tank underneath. The water you run through the sink during the day collects there along with the waste. To flush the system you unstopper it and the rush of accumulated water is meant to propel everything down into a giant collection reservoir at the bottom of the building where things settle a bit before a big tanker truck comes and takes it away.

In practice, the stink of rotten food that builds up in the holding tank meant that it had to be thoroughly cleaned ever couple of weeks, a task few relish. And these days the Garcheys often get bunged up. (Hands up anyone who’s shocked at that. Anyone? Anyone? Beuller?). In part this is because back when the system was conceived housewives were home home during the day and much more water was run through the pipes much more consistently. Also these days we flush way too many nappies and wet wipes that clog things up. (A problem for London's sewers in general.) Now a lot of the Garcheys in Barbican kitchens have been removed and capped. However, some are still in operation and the truck still comes to suck up the gunk from the remaining working units. Apparently some of the original engineers who installed them have retirement jobs cleaning out the systems that are still in use.

Another example of well-intentioned but ultimately failed design are the greenhouses. Built over a flat, leaky roof, they were, unsurprisingly, not a hit with the downstairs neighbours.

I've alluded a few times to the notion that the Barbican can be tricky to navigate. In fact, that’s a bit like saying Hitler had a mild interest in territorial expansion. The Barbican is notoriously difficult to get through and around. This is in part due to a key architectural feature of the estate, the elevated walkways known as Highwalks. One of the big ideas about city planning at the time was to separate pedestrians from vehicle traffic, and in the Barbican this was accomplished by raising pedestrians up above street level in dedicated walkways. The plan was intended to be incorporated all over the city, though they're actually relatively rare outside the Barbican. The Highwalks also increase difficulties in navigation when it’s not immediately apparent how to get onto or off them. Then there’s the large and uncrossable ornamental lake, the randomly encountered locked gates, the uncountable number of stairwells and the miles of same-y looking rough concrete corridors, some of which curve on a wide radius making things even more disconcerting. It’s no wonder the Barbican is sometimes used as a case study in urban way-finding. (Listen to this podcast!)

A small part of the Barbican

Like this one.

When they eventually managed to formulate a plan for using the space the goal was not simply to cram it with as much housing and commercial space as possible. In fact, the aim was much loftier than that. The Barbican was meant to be a physical symbol of how London could rise again after the destruction of the war - a grand showpiece and a bold statement. The architects - Chamberlin, Powell and Bon - set out their intention to create a complete machine for living, with residents able to enjoy modern conveniences, green spaces, and services like libraries, shops, theatres and cinemas, all in a densely developed but also open, inviting highly designed ecosystem combining residential and civic functions with modern design.

Private waterfall, anyone?

Part of that modern design is the architectural style of the Barbican - it’s one of the most prominent examples of Brutalism in the UK, being constructed almost entirely from brick and concrete with exposed aggregate. Interestingly, one might assume the exposed concrete seen all over the Barbican is the actual structural material, but it’s actually a layer added after construction, dried for 21 days, and then pick-hammered by Italian stone masons to create the distinctive texture.

You can see a bit of the concrete here - above these flats that overlook the lake. Not bad!

There are even a few hidden mewses with houses that enjoy way way off-street parking and gardens.

Luckily, one of the Barbican’s 4,000 residents is also one of GSWPL’s more astute readers, and on hearing of my interest in the estate as a whole he extended an invitation for lunch and a private tour with a couple other friends one Sunday in rainy December. This was especially excellent because it meant not just a lovely lunch, but a visit inside a real Barbican flat, and a tour around the estate led by a highly knowledgeable guide in possession of the all-important resident’s key, allowing access to all kinds of places mere plebeian mortals could not presume to tread. The invitation also came accompanied by a painstakingly detailed set of directions for getting from the tube station to the exact location of the flat - no small feat in a complex that is renowned for being murderously difficult to navigate. I’m happy to report I was able to find my way with only one small back-track required.

The flat in question is on the top level of Andrewes House, one of the terrace blocks that make up the central heart of the complex. See those barrel-vaulted roofs on the left? One of those!

There are other modern conveniences in the flats that we'd take for granted right now but were, at the time, quite unusual. For instance the kitchens are open to the living and dining area and were designed by marine galley engineers to maximise what was considered to be very little space. Bathrooms featured showers - also not common for the time. Balconies are also included, with a lot of flats having one at each end, a real luxury even today. And many of the Barbican's flats are housed in giant tower blocks, once the tallest residential buildings in Europe. However, these unusual modern touches, coupled with the estate's location in the middle of a bombed out neighbourhood meant that getting people to move to the Barbican was hard work. Difficult to believe from our perspective in 2018, when a 440 square foot studio flat in one of the estate's terrace blocks goes for more than half a million quid.

The all concrete construction makes for a very solid structure but comes with some disadvantages. I knew an architect who was a big fan of Brutalism (architects are often the only champions of this style). One of the reasons he gave for his fondness is that, for an architect, it's a real challenge. When you're pouring concrete that's both the structure and the outer finish of the building, there's nowhere to hide if something goes wrong. There's no covering mistakes behind a layer of plasterboard. Everything has to be designed in from the beginning, including the wiring, so even something as (relatively) minor as a light fixture or a plug socket has the be included at the earliest stage. In the case of the Barbican this means that all the wiring and plumbing is literally set in stone. It can't be changed, and if it was installed incorrectly or breaks, there's really nothing to be done. And forget getting fibre broadband or smart electric or water meters or extra power to anywhere.

If this all seems a bit Big Brother, consider the many advantages of living in the Barbican. For instance, you’ve got London's second largest conservatory on your doorstep. (It was designed to enclose and disguise the fly tower of the theatre!) It used to be open every day, but sadly it’s now just on “selected Sundays and Bank Holidays”.

Naturally our Sunday visit was carefully timed to coincide with the conservatory’s opening hours, so we got to wander through and meet the resident turtles. It’s really lovely, and I can see why my resident guide laments no longer being able to slip in and out on a whim.

And on the topic of waste collection, surely one of the most interesting quirks of the Barbican must be the infamous Garchey disposal system. Intended to eliminate those rubbish collections I mentioned, the Garchey is like a super-charged in-sink garbage disposal designed not just for wet garbage like potato peelings and coffee grounds but almost everything else except really large and bulky things. Even cans and bottles are fair game (keep in mind this was pre-recycling). With a Garchey system all that waste is put down the sink drain where it sits in a holding tank underneath. The water you run through the sink during the day collects there along with the waste. To flush the system you unstopper it and the rush of accumulated water is meant to propel everything down into a giant collection reservoir at the bottom of the building where things settle a bit before a big tanker truck comes and takes it away.

Here's a grainy cut-away of a Garchey sink.

Another example of well-intentioned but ultimately failed design are the greenhouses. Built over a flat, leaky roof, they were, unsurprisingly, not a hit with the downstairs neighbours.

Those expanses of curved brown-ness are actually the glass walls and roof of a the greenhouse space. Also, those curves make it impossible to clean the glass. (Ok, ok, I know they're not actually IMPOSSIBLE to clean. You could, for instance, design bespoke window scrubbing drones that suction to the glass and work their way over the surface like some kind of semi-autonomous Roomba/catfish hybrids. Maybe someone should call James Dyson.)

"The Barbican takes the City’s ancient complexity and expands it over three dimensions – you can go up and down as well as backwards and forwards, so wandering around the Barbican becomes an adventure. Curves envelope you, towers loom, narrow pedways disappear under pedestals and re-emerge as wide walkways enlivened by beds of wild flowers.” (Source)However despite its shortcomings, Barbican residents tend to be a loyal lot who appreciate the fantastically central location, the sense of community, the many cultural facilities, and the acres of private gardens. Sure, you've got to equip guests with flare guns so you can come rescue them when they get lost on their way back to the tube station, but who else in London can brag about being able to flush empty baked bean tins down the sink?