Public Service Announcement: We here at Go Stay Work Play Live World Headquarters (A.K.A. GSWPLWHQ) understand these are trying times and our absolute priority is to ensure the health and safety of Astute Go Stay Work Play Live Readers. To that end we are committed to continuing to deliver hastily-researched blog posts about whatever might have been happening before the End of Days arrived, or whatever happens after, or whatever random bullshit happens to cross our minds. We're certain that ten minutes of distraction delivered on our usual intermittent and unpredictable schedule will help while away the hours while you contemplate what's next on Netflix and which of your loved ones will be the first on the BBQ when the ramen noodles run out. And now, on with the blog.

There are few things more certain to stir a positive and patriotic response in the average Brit than the sight of a scarlet-clad Chelsea Pensioner. They are an unassailable icon.

For overseas or under-informed Astute Go Stay Work Play Live Readers, the Chelsea Pensioners are residents of the Royal Hospital Chelsea, a retirement and nursing home for former members of the British Army located in Chelsea, London. The Royal Hospital was established in 1682 by Charles II as a home for army veterans. Until that time no official provisions were made to support old or injured soldiers and Charles was said to have remarked, "Those who have served the king, the king shall then serve them". Quite right. (And don't bother questioning the source of that quote because I heard it from the lips of King Charles himself. Sort of. See below.)

Designed by Sir Christopher Wren, the hospital buildings are part of an impressive 66 acre Thames-side estate surrounded by high walls and iron gates. When it was built most people would have arrived by river, so what we think of now as the front - facing Royal Hospital Road - is really the back. The site is probably best remembered as the location of the famous Chelsea Flower Show but it’s not generally known that the grounds are normally open to the public during the day (including a post office and café) and tours of the grander buildings are also available. Recently the Royal Hospital also started offering evening “candlelit tours” as another way of showing off the place. Having seen these tours advertised, I quickly snapped up some tickets and planned a visit with the always-willing Piran and the visiting Canadian Don for a peek into the life of the famous pensioners.

(Hastily inserted note from GSWPLWHQ: Obviously there are no tours or public access during the Zombie Apocalypse, but I wrote this post back when you could still move around on the street and even go to the pub. Ah, the good old days, last Wednesday. To be known by history as "The Infectious Old Days".)

Part of what’s interesting about the Royal Hospital buildings are that they’re still being used today for the very same purpose for which they were constructed more than 300 years ago, barring a few renovations along the way. The first residents were admitted in 1692 and are still technically known as in-pensioners to distinguish them from out-pensioners who received financial assistance but didn’t live on site. The hospital is currently home to about 300 men and women. (Of course men have been eligible for residency since the hospital’s founding; the first women arrived in 2009). To be eligible to join the ranks of the Chelsea Pensioners an applicant must be a former soldier or non-commissioned officer of the British Army who served for at least twelve years, be at least 65 years old, and be in receipt of an Army or disablement pension. They also have to be healthy enough to live independently in the famous “long wards” (more on them later) and be free of financial obligations to support a spouse or other family. If accepted they surrender their army pension (which is used to fund their stay) though they do retain their state pension. Residents are also assured of later life care in a separate infirmary on site.

Our tour was on a rainy Wednesday evening and it was clear from the start that the Candlelit Tours are new, and they’re still working out the kinks. The Royal Hospital’s grounds are extensive, so finding the entrance gate was a bit of a schlep (did I mention it was raining?). Being directed to a different gate a long-ish walk away was disheartening. And then being sent back to the gate where we’d started was, well, let’s just say there may have been some strong language employed by your humble blogger. When we finally found the right spot we were greeted by a Chelsea Pensioner named Peter, wearing his scarlet coat and carrying a handheld lantern equipped with a rather dim LED candle. I suppose that’s the “candlelit” part. (Note to RHC: I can help you with that. Internally lit handheld props are genuinely one of my core competencies. Call me.)

Peter was lovely and informative, leading us through the grounds and into the state apartments for our first stop where we were greeted by... *heavy sigh*… an actor portraying King Charles II. I’ve said it before, but I truly hate this trend of presenting costumed live action characters from the past to spice up a tour. I suppose it’s nice for the actors who get the role - good steady work - but I just find it cringe-y. Usually these sort of encounters are relatively short but King Charles had a lot to tell us that night, including a large measure of Civil War and Restoration history, and it seemed to go on forever.

Eventually we were released to make our way to the chapel, which sits opposite the Great Hall in the centre of the complex. It being dinner time we didn’t get to see inside the Great Hall, where the residents take all their meals, but which I imagine its pretty much the same as the Great Hall from Hogwarts but with more Ovaltine and false teeth. En route to the Chapel we passed the Birkenhead Memorial, a little-known tribute to the men of H.M.S. Birkenhead, which broke up off the coast of South Africa in 1852. You’ve probably never heard of the Birkenhead, but you know its legacy. After the ship foundered on the rocks, “there were not enough serviceable lifeboats for all the passengers, and the soldiers famously stood firm on board, thereby allowing the women and children to board the boats safely and escape the sinking… The soldiers' chivalry gave rise to the unofficial 'women and children first' protocol when abandoning ship…” (Wikipedia. Obvs.) This practise is also known as the "Birkenhead drill”, and came to describe courage in face of hopeless circumstances.

The Chapel is undeniably impressive, designed by Sir Christopher Wren and featuring a vaulted roof and a very accomplished mural that was apparently painted freehand inside the concave surface of the quarter dome at the end of the room. Demoralisingly, the chapel portion of the tour was conducted by a living representation of Christopher Wren himself, who was even more loquacious than King Charles and somewhat frenetic, with the added indignity that he stumbled over his lines a bit and passed on some very dodgy information about the engineering properties of the arched roof that had me screaming silently. Nonetheless the room is lovely and eventually Christopher Wren stopped talking.

Things picked up when we left the chapel and moved on to the area where they’ve preserved two of the original rooms where the pensioners would have lived when the building was new. Called berths, each man was assigned a 6’ x 6’ space with walls reaching only partway up, arranged in rows on a long corridor in the main hospital building. Called the long wards, each man’s berth held just a small single bed, table, and chair, with a shutter opening onto the communal corridor. Even the famous red coats had to be hung on pegs outside the door. Eventually the berths were expanded to 9’ x 9’ but much of the space on the long wards has always been devoted to the corridor outside the berths, equipped with comfortable chairs, tables and tea-making facilities. The small size of the berths and the congenially appointed corridors means that the residents are encouraged to move around and socialise more.

The berths are the heart of the Royal Hospital and the life of the pensioners, but until recently their spartan nature meant that 36 elderly residents shared one communal bathroom at the end of each corridor. Because of this, the long wards underwent an extensive renovation, completed in 2016, that provided pensioners with enlarged bedrooms including generous windows, en suite facilities, and a separate small study. The architects cleverly maintained the wide social corridor and left the walls to the outer study lower to maintain the connection to the shared space.

We didn’t actually tour the wards of course (that photo is from the interwebs) but at the end of the evening we were invited to the residents’ private lounge for a glass of wine and a natter with Peter and Carl, and that was genuinely the best part of the visit. Talking with real Chelsea Pensioners we got a true sense of what their life is like. “Happy as a pig in muck” was the quote I wrote down, and I can understand why. The place is comfortable, the meals are apparently so lavish that it’s hard to maintain a fighting man’s physique, and they get Sky Sports for £10 a month.

As I mentioned, the Chelsea Pensioners are universally revered, and Peter and Carl confirmed that when they’re at the pub in their scarlet coats they never have to buy their own drinks. This can, however, lead to abuses of the system. Being a Chelsea Pensioner is not a life appointment for some. For instance, we learned of one who’d been chucked out for charging tourists £5 each for selfies with him, though I’m sure that’s a very rare situation. For the most part the Chelsea Pensioners play by the rules and enjoy their lives. They also pursue their own hobbies and are very active in the wider community. Every week there’s a bulletin of events requesting their attendance and each resident is expected to volunteer for an appropriate number of appearances. And being ex-military, they’re also used to being volunteered when circumstances require it. Though there’s certainly never any difficulty filling the seven seats they’re given for every home fixture of the Chelsea Football Club, with whom the Pensioners have a longstanding association. Chelsea Pensioners are also seen at Twickenham and Wimbeldon and make appearances at Parliament and Downing Street. It’s a far cry from the 17th century, when they were required to patrol the King’s Road with pikes as a public service.

Once we’d had a glass of wine, dried out, warmed up, and quizzed Peter and Carl about their lives, all that was left was to forget to take our own selfies with them and head back out into the rain. Tragically, it was bizarrely difficult to find a pub that was still serving food by the time we left, so we had to content ourselves with a warm seat by the fire at The Antelope where we attempted to keep body and soul together sharing out a single scotch egg I had in my bag, supplemented with six bags of Mini Cheddars and several pints. We probably should have just brought Carl and Peter with us. I bet nobody tells a Chelsea Pensioner that the kitchen is closed!

**********

There are few things more certain to stir a positive and patriotic response in the average Brit than the sight of a scarlet-clad Chelsea Pensioner. They are an unassailable icon.

A group of Chelsea Pensioners parading in the Opening Ceremony of the

London 2012 Olympics. Remember that?

London 2012 Olympics. Remember that?

Designed by Sir Christopher Wren, the hospital buildings are part of an impressive 66 acre Thames-side estate surrounded by high walls and iron gates. When it was built most people would have arrived by river, so what we think of now as the front - facing Royal Hospital Road - is really the back. The site is probably best remembered as the location of the famous Chelsea Flower Show but it’s not generally known that the grounds are normally open to the public during the day (including a post office and café) and tours of the grander buildings are also available. Recently the Royal Hospital also started offering evening “candlelit tours” as another way of showing off the place. Having seen these tours advertised, I quickly snapped up some tickets and planned a visit with the always-willing Piran and the visiting Canadian Don for a peek into the life of the famous pensioners.

(Hastily inserted note from GSWPLWHQ: Obviously there are no tours or public access during the Zombie Apocalypse, but I wrote this post back when you could still move around on the street and even go to the pub. Ah, the good old days, last Wednesday. To be known by history as "The Infectious Old Days".)

Statue of Charles II in the style of a Roman general, in the central courtyard. Designed by the famous (and excellently named) sculptor and wood carver Grinling Gibbons.

Our tour was on a rainy Wednesday evening and it was clear from the start that the Candlelit Tours are new, and they’re still working out the kinks. The Royal Hospital’s grounds are extensive, so finding the entrance gate was a bit of a schlep (did I mention it was raining?). Being directed to a different gate a long-ish walk away was disheartening. And then being sent back to the gate where we’d started was, well, let’s just say there may have been some strong language employed by your humble blogger. When we finally found the right spot we were greeted by a Chelsea Pensioner named Peter, wearing his scarlet coat and carrying a handheld lantern equipped with a rather dim LED candle. I suppose that’s the “candlelit” part. (Note to RHC: I can help you with that. Internally lit handheld props are genuinely one of my core competencies. Call me.)

Peter and his lantern and his smart scarlet coat. He’s wearing a less formal hat here called a shako (“shake-oh”) instead of the traditional tricorne. The pensioners normally wear a more casual dark blue uniform and shako around the hospital and local neighbourhood for day-to-day activities, reserving the scarlet and tricorne for trips further afield and special occasions.

“King Charles II”. With all due respect Your Majesty, please move it along a bit.

Approaching the Great Hall (on the left) and the Chapel (on the right)

The Chapel. Perhaps better viewed in daylight when the large windows could show off the woodwork better. (Woodwork that was carved by the aforementioned Grinling Gibbons!)

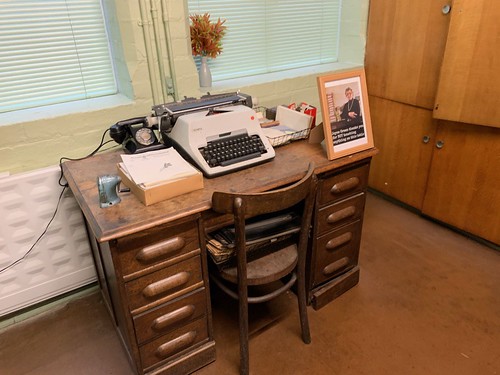

Carl, another pensioner, with Peter, in one of the small “heritage berths" on display in the museum area of the Hospital. Carl is wearing the everyday “blues” uniform.

The long wards after the renovation, with Wren's original oak panelling carefully preserved. Note the scarlets still hanging outside the doors. Old habits, I guess. The total number of berths on existing long wards was reduced in the renovation, but more were created in a separate building.

Nice library, big tv, comfy couches. What more could you want on a rainy evening?

Once we’d had a glass of wine, dried out, warmed up, and quizzed Peter and Carl about their lives, all that was left was to forget to take our own selfies with them and head back out into the rain. Tragically, it was bizarrely difficult to find a pub that was still serving food by the time we left, so we had to content ourselves with a warm seat by the fire at The Antelope where we attempted to keep body and soul together sharing out a single scotch egg I had in my bag, supplemented with six bags of Mini Cheddars and several pints. We probably should have just brought Carl and Peter with us. I bet nobody tells a Chelsea Pensioner that the kitchen is closed!