Hold onto your hats kids, the time has come to dive into that most English of past times… cricket! I've been waiting to report on cricket until I had the chance to go to an actual English cricket match with and actual English cricket fan, and the opportunity final came this week when I succeeded in browbeating my lovely friend and Olympics colleague Ted into visiting the Oval on an uncharacteristically hot, dry and gorgeous Monday evening. Ted is a proper lifelong cricket fan, so I was particularly touched that he got the train all the way in to London for a trifling evening game. Thanks Ted!

Cricket is a huge subject and one that I find quite interesting, so I'm going to break things up into a couple of posts so that I can cover what I want to, and so your coffee doesn't get cold while you're reading. Settle in.

First, let's review the fundamentals of the game. Cricket is a ball-and-bat game played by teams of eleven players on a large grassy, field. The teams take turns batting and fielding, with the batting team trying to score runs and the fielding team trying to dismiss the batters. In the middle of the field, which interestingly has no official size or shape, but is generally a big oval, there's a rectangular 3 x10 metre area called the pitch where most of the action takes place. At either end of the pitch is a set of stumps - three stout stakes driven into the ground, side by side. Resting on the stumps but - critically - not attached to them are two round wooden peg sort of things called bails. The team that's batting fields two batsmen (not, heaven forfend "batters") at a time, who stand at opposite ends of the pitch. During play, the fielding team's bowler will throw the ball towards one of the stumps (or "wickets") and the opposing team's batsman will attempt to hit it away to stop it from striking the stumps. If the ball hits the stumps and one or both bails is dislodged, the batsman is dismissed. Simple.

In order to score runs the batsman and his partner run back and forth between the stumps after the ball is hit. Each time the batsmen change places, one run is scored. If the fielding team catch a batted ball before it hits the ground, the batsman who hit it is dismissed. (And despite the ball being as hard as a baseball, the players do not wear gloves.) If the ball bounces before it's caught, the fielders attempt to retrieve it as quickly as possible and throw it back towards the stumps. If a ball thrown back at the stumps hits them and dislodges a bail, the batsman is out. Or if the ball is returned and caught by a player who then knocks the bails off himself while holding the ball, the batsman is similarly dismissed.

A closer look at one end of the wicket

In addition to scoring runs a few at a time by running back and forth between the wickets, a batsman can score four points at once if he hits the ball far enough that it rolls up to and hits a low boundary marker around the edge of the field. If he hits a ball clear over the boundary - like a home run - that's worth six points. These scoring plays are known, not surprisingly, as "boundaries".

Every time six balls are bowled (a division of the game called an "over"), the direction of bowling changes. This means that depending on where the batsmen end up at the end of an over the same batsman may continue batting, or the other guy may end up "on strike" (not a labour disruption, but the term used to indicate that he's the guy being bowled to.) And that's pretty much it. Whoever has the most runs at the end wins, though getting to the end can be quite a marathon, as we shall soon see. And of course there are approximately 11,436 other rules that I've left out for clarity, like the six other ways a batsman can be dismissed (five of which are exceedingly rare and one that's quite common, the often controversial lbw - "leg before wicket")

Every time six balls are bowled (a division of the game called an "over"), the direction of bowling changes. This means that depending on where the batsmen end up at the end of an over the same batsman may continue batting, or the other guy may end up "on strike" (not a labour disruption, but the term used to indicate that he's the guy being bowled to.) And that's pretty much it. Whoever has the most runs at the end wins, though getting to the end can be quite a marathon, as we shall soon see. And of course there are approximately 11,436 other rules that I've left out for clarity, like the six other ways a batsman can be dismissed (five of which are exceedingly rare and one that's quite common, the often controversial lbw - "leg before wicket")

There are several forms of cricket currently played professionally. Traditionally, each team bats for two complete innings (a word used, disconcertingly, for the singular as well as the plural. As in "England had an excellent innings yesterday. We'll see if the Australian innings can top it today.") To complete an innings one team bats until 10 of the 11 batsman have been dismissed, leaving one man "not out". Because two batsman are required to play, a team with ten men out cannot continue batting and their innings is over. Then the other team bats until ten wickets have fallen, after which the other team has their second innings, and so on. As you can imagine this process takes some time, but there is a limit. For instance, an international "test match" (the highest level of professional play) is normally limited to five days, though it can end sooner if all four innings are completed. If the innings are not complete by the end of play on the 5th day, the match is declared a draw. It's important to note here that a draw is very different than a tie. A tie would occur if the score was even at the end of the last innings, which is quite rare. On the other hand, playing for a draw can be a legitimate strategy for an underdog team but it does make it possible for a game of cricket to last for five days and still end up with no winner. It's just one of the many confounding but charming things about the game.

(Aside: There have been experiments with "timeless test matches" - ones with no time limit where play continues until four complete innings are played. The trouble with this is that when a batsman hits the ball he's not actually required to run; he'll only run if he feels there's a good chance of scoring safely. Therefore it's possible for a batsman to play very defensively, and bat almost forever. The last timeless test match was played in 1939 between England and South Africa when the game "was abandoned as a draw after nine days of play spread over twelve days, otherwise the England team would have missed the boat for home.")

In the 1960s quicker forms of the game appeared with a shorter time limit or fixed number of overs, in order to speed up play. There are popular one-day matches, which are usually limited to 50 overs (300 balls bowled). The newest and quickest form of the game is called Twenty20, introduced in 2003. In a Twenty20 game, each team only bowls 20 overs (120 balls) and the game is usually finished in about 3 hours, meaning it can be played in an evening. It's a very different sort of thing to a test match, often with more hitting and potentially more excitment. That's the kind of game Ted and I went to on Monday night, despite Ted's protests that it's not really proper cricket at all. (Think of it like the difference between a real NHL hockey game with the potential for unlimited overtime, and a ten minute game of 3-on-3. Not really the same at all is it?)

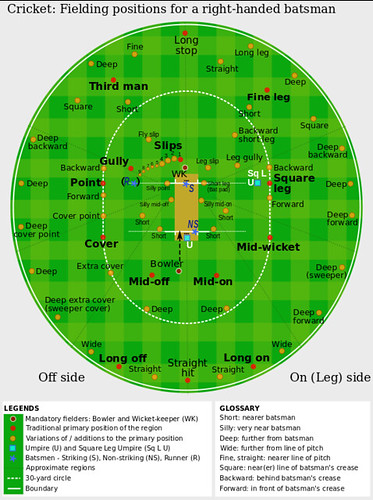

People who play cricket are called cricketers, and cricketers are usually divided into batsmen, bowlers and all-rounders. Though a player may specialise as a batsman or bowler, that doesn't mean that's all he does. Everyone bats, though bowlers often appear late in the batting order because they're often, but not always, kind of crap batsmen (again, like baseball). Several bowlers are used in any game but unlike pitchers in baseball they don't just lounge around on the sidelines when they're not pitching. There are only eleven players on the team so if a bowler's not bowling, he'll be fielding somewhere. It's a large field to cover with not many men, so the players move around a lot depending on who's batting, and what direction the batsman is facing, and whether the batsman is right or left handed. The captain of the team is the one who decides which player fields from where, and he's constantly directing them to adjust their positions to gain the best tactical advantage. And the names for the fielding positions are just fantastic: Square leg, Third man, Mid-wicket, Fine leg, Long off, Silly mid-on… lovely. These names are made more confusing because they're all related to the position of the batsman, so when the batsmen switches ends, the names of the positions move around. It's highly confusing, though I did manage to correctly identify a Fine Leg at one point, which Ted was appropriately impressed with.

Of the mainstream sports in England (football, rugby, and cricket), cricket is the second most popular, and, I think, the first most posh (not polo-and-fox-hunting-posh, but still...). After all, any game where you stop in the middle of the afternoon for tea would have trouble purporting to be a rough and tumble sort of a past time. In fact, during a day's play it's normal to stop after two hours for lunch, then after another two hours for afternoon tea. Perhaps this constant stopping to eat and drink is why in times gone by cricketers were not known for their physical prowess. Apparently even professionals used to be rather heavy and slow, though now they're all proper athletes with training regimes and, you know, abs. Ted claims that it's far more common now than when he was a boy to see a fielder run a player out by hitting the wicket with a ball thrown from deep in the field. It's quite a feat, really. The stumps are only 9 inches wide head on, and from an angle they're much narrower. Also, these days deep fielders are much more likely to chase down a batted ball heading for the boundary in order to stop it hitting for four points. In the old days, a player might have to put his drink down in order to make a play like that.

Ricky Ponting being run out. Look at that bail fly! Ricky Ponting is a famous Australian batsman. As captain of the Australian team he was once bowled out in an Ashes test match against England (more on the Ashes next week) by a substitute local player who'd been brought in to field because one of England's players was injured. It's a famous moment in the history of the game. Interestingly, Ponting is now playing for the Surrey Cricket Club, one of the teams that I watched on Monday night, so I got to see him bat.

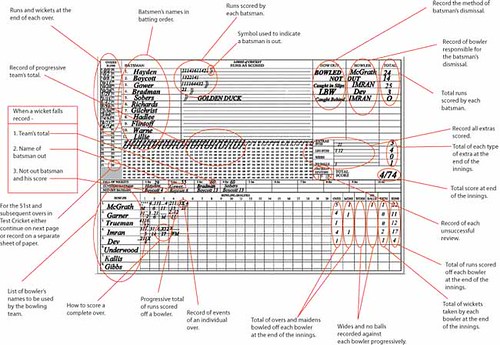

Similar to baseball / softball in North America, there are many levels of play in cricket starting at the highest, International Test Cricket, played by the best players in the country, through professional county leagues similar to AAA baseball and on to the cricket equivalent of slo-pitch beer leagues and even down to pick-up games similar to street hockey. Also like its cousin baseball, cricket is mad for statistics. Being a game that unfolds slowly, and with a mostly fixed number of outcomes for each ball, it lends itself to that obsessive sort of record-keeping that involves knowing, for instance, how many boundaries a particular batsman has scored against left-handed bowlers after tea break in the fourth day of a test match when playing south of the equator and batting into the sun, and so on.

Watching a quick Twenty20 match at the Oval reminded me a lot of going to a Winnipeg Goldeyes game. It was a warm evening, and the crowd was happy, and there's beer and junk food to eat, and the game unfolds at the same generally leisurely pace that means you can still have a nice conversation and learn about the intricacies of the lbw rules or go stand in line for another beer without missing much. Interestingly, the announcer doesn't butt in nearly as much, perhaps because there usually isn't a parade of new batters to announce regularly. Unlike outs in baseball, which happen pretty regularly, the fall of a wicket is a quite momentous thing.

As for the cricket grounds, the Oval is not as famous a cricket ground as Lord's, which is the other large cricket ground in London and is often called the Home of Cricket. Still, the Oval has a certain gritty urban charm, and is conveniently situated a scant 20 minute bus ride from home, so it's ok in my book.

The Pavillion at the Oval. That black screen is there so the batsman can see the ball against it as it's bowled. The screen moves back and forth because the position of the wickets on the field is not fixed. Groundskeepers move it around between matches so it doesn't get all worn out in the middle of the field. Weird, but oddly sensible too.

Despite the presence of a world class player like Ponting, Surrey were crushed by the visiting team from Essex. Surrey scored 148 runs in their innings, which was a bit weedy. Essex went on to match that number after losing only two wickets and when they got their 149th run, the game was over. (Full scorecard here.) This is just like the way a baseball game ends. Regardless of how may men are out, when the home team (batting last, of course) score one more run than the other team it's all over. Ted declared it may have been the least interesting Twenty20 match he'd ever seen, though he's not a fan of Twenty20 anyways, so I have no idea how resounding a condemnation that really is. I thoroughly enjoyed the evening.

And that's my best crack at giving you an overview of cricket. Next week, we'll look more at the culture of the game, including talking about The Ashes, and Test Match Special and maybe some famous players and whatever else pops into my head. I bet you can't wait.

2 Comments:

Thanks a lot for share your great post about sport's.it is informative post for cricket.This site published important topic of cricket.i hope this site give more important information.i wish all is well.

Post a Comment