Astute GSWPL readers will remember that I'm a big fan of London Walks. It's a rare day when I fork over my £9 for a walk and feel like it wasn't well worth it at the end. Most London Walks follow a fairly standard pattern - arrive at the appointed tube station, hand over your money to the guide who will be waiting there, follow that person around for a couple of hours learning more about London than you thought possible, and repeat as necessary. There is, however, one particular and quite different walk that's been on my list for some time now - the Thames Beachcombing walk.

(Aside about the London Walks website... I love London Walks. I really do. I think they do great work and deserve all the praise they get. However, the writing on their website is just a tad over the top - and this is coming from someone you know is not above a bit of purple prose on occasion. Certainly the website functions well enough - you get the information you need about what walks happen on what days and what times. But when you start to read the descriptions of individual walks the system falls down a bit. Yes, you learn what each walk is about, but the more descriptions you read the more you realize that EVERY walk in the schedule is described in such ridiculously glowing terms you start to get just a tad suspicious. I submit the following randomly selected quotes in evidence, all describing different walks:

So the walk is called "beachcombing" but the more proper, more London-y term would be "mudlarking". As the ever-faithful Wikipedia says: "A mudlark is someone who scavenges in river mud for items of value, a term especially used to describe those who scavenged this way in London in the late 18th and 19th centuries." These days the term mostly applies to people with metal detectors looking for old coins or other items of value, and dilettantes like your humble blogger.

Key to the whole activity is the fact that the Thames in London is tidal, which means that twice a day the tide comes in, possibly bringing or uncovering new stuff with it, and twice a day the tide goes out, leaving large stretches of rocky beach for exploring. Of course you don't need to go on a guided walk to explore the shoreline. I've been down on the banks of the Thames a few times already - there are access gates and stairs that lead down from the embankment in a few spots and anyone can go down if they want to. The difference with a London Walks trip to the beach is that you are accompanied by an intertidal archeologist, a particular species that I confess total ignorance of prior to last Saturday. And having that person along for the ride makes all the difference.

Our guide was Fiona, described in the typically breathless fashion of the London Walks website as "the world's leading authority on this stretch of Thames foreshore" (that's also highlighted in bright yellow, in case you might miss it). Fiona turned out to be a lovely woman who had indeed been studying the tidal Thames for much of her career and had come to the walk more or less straight from the airport where she'd got off an overnight flight from some kind of dig in South Africa. So she was not only qualified, but also dedicated.

We started on a cold but sunny Saturday morning at Mansion House station and quickly made our way towards the river, with Fiona spouting typical London Walks info the whole way... with one slight difference. I've done quite a few walks and I've never before been warned of the possibility of gruesome death as a result of the walk's activities. In this walk though, Fiona took great pains to warn us about the dangers of Weil's Disease, a malady charmingly know by a few other names like mud fever, swamp fever, haemorrhagic jaundice, swineherd's disease, and sewerman's flu. It's a bacterial infection transmitted through contact with animal urine, usually in contaminated water. Despite its reputation as a deadly and fetid swamp, the Thames has actually come a long was since the days of the "Great Stink". It's a healthy, living river again, with more than 120 different species in it. Nonetheless there's still a risk, as evidenced by the unfortunate death in 2010 of one of Britain's Olympic rowing hopefuls, Andy Holmes. So Fiona was quite insistent about keeping us safe, and had boxes of rubber gloves that she made everyone put on before we got down to the beach.

The history of London is inextricably linked with the history of the Thames; the city just wouldn't be here without it. The fact that the river has strong tides is what made the Romans settle here instead of on a nice bit of coast somewhere like Brighton, where they could have enjoyed a walk along the pier and a stick of rock candy before heading north to try and subdue those pesky Picts. The tide meant that ocean-going supply boats could ride the tide into the city for unloading before riding it back out again, which turns out to be quite handy when you're running an empire. And the river back then was much wider and curvier than it is now. A lot of the curves are gone, meaning that the current is unexpectedly fast and potentially deadly. During the Queen's Diamond Jubilee River Pageant last summer they had to raise the Thames Barrier to slow the current and make the river safe for the man-powered boats. And generations of engineers have reclaimed so much land from the river that this street is now more than 500 feet from the current embankment.

The river has been affected by man in other ways too. The tides today are measurably greater than they were hundreds of years ago; high tide is higher and low tide is lower. In Roman times its estimated the tide measured about six and a half feet, now it's more like eight. Global warming is the likely culprit. You can see this in the architecture around the riverbank, particularly in the causeways built to allow you to board a boat safely (any drily) at any tide.

If the history London depends on the Thames, then a lot of the history of the Thames surrounds its bridges. It was the Romans (of course) who built the first bridge across the Thames, approximately where the modern London Bridge stands today. It was followed by a succession of bridges in that same area. The medieval stone bridge is perhaps the most famous incarnation, and the most long-lived. It's the one you see in pictures with the shops and houses and heads-of-traitors-on-a-pike on it. That bridge was built on 19 heavy stone piers that obstructed the flow of the river so much that the water level could be six to nine feet higher on the upstream side than on the downstream. The build-up of slower-flowing water on the upstream side of the bridge also contributed to more frequent freezing of the river, and to the Frost Fairs that accompanied those freezes. And the dangerous flow of water through the bridge piers made passing under the bridge in a boat recklessly foolish. It was said the bridge was "for wise men to pass over, and for fools to pass under." Though those wise men had better not be in a hurry. Since London Bridge was the only bridge across the Thames (in London) until the 19th century, it was often so congested it could take hours to cross.

For centuries the Thames was the main artery through London and often the best way to travel quickly and safely through the city. At some times in its history there was so much river traffic that you could actually could cross the river by hopping from boat to boat. And the port became so busy that a ship arriving with cargo might have to wait up to a year to clear customs before it could be unloaded. In the 1850s London was the world's busiest shipping port and shipping remained a vital industry until as late as the 1960s. The advent of shipping containers killed the port of London by diverting container ships to outlying ports like Tilbury where they had room for the large machinery needed to load and unload containers and acres of space to store them. There's still some commercial traffic on the river today - garbage collection on barges, for instance - but it's mostly used for recreation now (Weil's Disease notwithstanding).

I started out to tell you about mudlarking, and all I've done so far is prattle on about the history of the Thames. But really, that history is actually central to the activity. The whole reason that the riverbanks contain enough interesting effluvia to make it worth risking haemorrhagic jaundice to poke around on them is precisely because of the incredibly ancient and teeming history of the river and the people who've lived on and around it for hundreds (well, actually thousands) of years.

But back to the riverbank. Suitably gloved up, we were set loose on a section of the Thames foreshore just in front of the Tate Modern, where there's a handy gate in the railings on the embankment and a very comfortable stone staircase that leads right down to the beach. Fiona let us poke around on our own, but did tell us the rules. First and foremost - no digging allowed. Digging would require a Thames Foreshore Permit. And we're not only talking about shovels-and-backhoes kind of digging either. Using any kind of implement to scratch the surface is considered digging, so we were even warned against nudging things around with our feet. Nonetheless, the Port of London Authority did not descend in black helicopters to arrest anyone in our tour.

Fiona encouraged us to grab anything that looked interesting (we'd been warned ahead of time to bring a bag to carry what we collected). And after about twenty minutes she gathered us up and had us lay out our treasures on a few heavy wooden posts sticking up from the riverbed, so she could tell us about what we'd found. That's the great advantage of mudlarking with a pro. You might find something interesting on your own, but would you really be about to identify it? Or understand how interesting it really is?

The most common finds are shards of crockery, animal bones, bits of ship-related metal like nails, and pieces of clay pipes. These clay pipes are a particular favourite. Tobacco smoking was introduced to England in the late 16th century, and by the 17th century disposable clay pipes pre-filled with tobacco were as common as cigarette butts are today. The pipes used to have very long thin stems and though it's exceedingly rare to find whole pipes these days, it's exceedingly common to find fragments of stem. And a few lucky people in our group found whole or partial pipe bowls. You can see a few pipe stem fragments just downstage of the boot in the middle of the photo above.

The area of shore we were on also once contained a glass bottle factory, so there were quite a few interesting chunks of glass found. I found an odd bit that Fiona thought might be part of the neck of a Codd bottle, named after the brilliantly-baptised Hiram Codd. He invented the Codd bottle for carbonated drinks, and versions of it are still in use today (in Japan, for instance...). The basis of the system is a metal or glass marble that resides in the specially shaped neck of the bottle. When the bottle is filled with a carbonated liquid the pressure inside the bottle forces the marble up against a rubber washer, sealing the bottle. Clever Hiram!

It's virtually impossible to find complete Codd bottles anymore because after growing weary of licensing his product Hiram took to allowing anyone to manufacture the bottles, as long as they bought the special marbles from him. This lead to a small cottage industry, mostly among children, in recovering discarded bottles in order to smash them and retrieve the marbles. (Please let's refrain from commenting on poor Hiram, his marbles, and the loss thereof.)

And that was the mudlarking. It was certainly more fun to do with someone who could actually tell you what you were looking at than to bumble around on your own with the tide coming in, and I came away with enough random facts and photos to write an over-long blog about it all. But eventually the fun wore off, mostly because it was actually quite chilly and I started losing feeling in my double-gloved fingers and my uncovered ears, and really just wanted to get somewhere warm and eat soup and then curl up with a few episodes of "Dr.Who".

And so I did.

(Aside about the London Walks website... I love London Walks. I really do. I think they do great work and deserve all the praise they get. However, the writing on their website is just a tad over the top - and this is coming from someone you know is not above a bit of purple prose on occasion. Certainly the website functions well enough - you get the information you need about what walks happen on what days and what times. But when you start to read the descriptions of individual walks the system falls down a bit. Yes, you learn what each walk is about, but the more descriptions you read the more you realize that EVERY walk in the schedule is described in such ridiculously glowing terms you start to get just a tad suspicious. I submit the following randomly selected quotes in evidence, all describing different walks:

"This is the cornerstone, the great seminal London Walk. Miss it and you've missed London." OR:I could go on. Lets just say that whoever writes the copy for the London Walks website needs to calm down a bit and probably cut back on the caffeine.)

"This is a great walk...they just don't come any better than this." AND:

"This one is really special." AND OF COURSE:

"Okay, time to take the gloves off with this one. GO ON THIS WALK."

So the walk is called "beachcombing" but the more proper, more London-y term would be "mudlarking". As the ever-faithful Wikipedia says: "A mudlark is someone who scavenges in river mud for items of value, a term especially used to describe those who scavenged this way in London in the late 18th and 19th centuries." These days the term mostly applies to people with metal detectors looking for old coins or other items of value, and dilettantes like your humble blogger.

A modern mudlark at work.

Our guide was Fiona, described in the typically breathless fashion of the London Walks website as "the world's leading authority on this stretch of Thames foreshore" (that's also highlighted in bright yellow, in case you might miss it). Fiona turned out to be a lovely woman who had indeed been studying the tidal Thames for much of her career and had come to the walk more or less straight from the airport where she'd got off an overnight flight from some kind of dig in South Africa. So she was not only qualified, but also dedicated.

We started on a cold but sunny Saturday morning at Mansion House station and quickly made our way towards the river, with Fiona spouting typical London Walks info the whole way... with one slight difference. I've done quite a few walks and I've never before been warned of the possibility of gruesome death as a result of the walk's activities. In this walk though, Fiona took great pains to warn us about the dangers of Weil's Disease, a malady charmingly know by a few other names like mud fever, swamp fever, haemorrhagic jaundice, swineherd's disease, and sewerman's flu. It's a bacterial infection transmitted through contact with animal urine, usually in contaminated water. Despite its reputation as a deadly and fetid swamp, the Thames has actually come a long was since the days of the "Great Stink". It's a healthy, living river again, with more than 120 different species in it. Nonetheless there's still a risk, as evidenced by the unfortunate death in 2010 of one of Britain's Olympic rowing hopefuls, Andy Holmes. So Fiona was quite insistent about keeping us safe, and had boxes of rubber gloves that she made everyone put on before we got down to the beach.

The history of London is inextricably linked with the history of the Thames; the city just wouldn't be here without it. The fact that the river has strong tides is what made the Romans settle here instead of on a nice bit of coast somewhere like Brighton, where they could have enjoyed a walk along the pier and a stick of rock candy before heading north to try and subdue those pesky Picts. The tide meant that ocean-going supply boats could ride the tide into the city for unloading before riding it back out again, which turns out to be quite handy when you're running an empire. And the river back then was much wider and curvier than it is now. A lot of the curves are gone, meaning that the current is unexpectedly fast and potentially deadly. During the Queen's Diamond Jubilee River Pageant last summer they had to raise the Thames Barrier to slow the current and make the river safe for the man-powered boats. And generations of engineers have reclaimed so much land from the river that this street is now more than 500 feet from the current embankment.

You can tell by the name that this street used to be much much closer to the water's edge.

The river has been affected by man in other ways too. The tides today are measurably greater than they were hundreds of years ago; high tide is higher and low tide is lower. In Roman times its estimated the tide measured about six and a half feet, now it's more like eight. Global warming is the likely culprit. You can see this in the architecture around the riverbank, particularly in the causeways built to allow you to board a boat safely (any drily) at any tide.

This is a causeway under Southwark Bridge. See the lines in the paving of the flat part that extends towards the water line? Those are areas where the causeway has been extended - three times - to try and reach the ever-receding low tide mark.

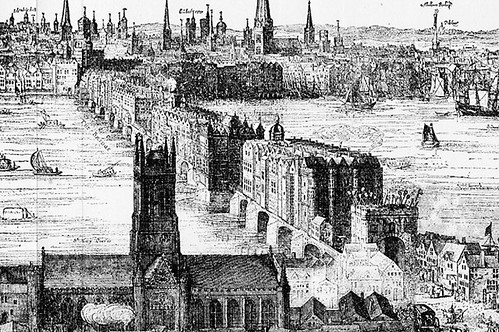

If the history London depends on the Thames, then a lot of the history of the Thames surrounds its bridges. It was the Romans (of course) who built the first bridge across the Thames, approximately where the modern London Bridge stands today. It was followed by a succession of bridges in that same area. The medieval stone bridge is perhaps the most famous incarnation, and the most long-lived. It's the one you see in pictures with the shops and houses and heads-of-traitors-on-a-pike on it. That bridge was built on 19 heavy stone piers that obstructed the flow of the river so much that the water level could be six to nine feet higher on the upstream side than on the downstream. The build-up of slower-flowing water on the upstream side of the bridge also contributed to more frequent freezing of the river, and to the Frost Fairs that accompanied those freezes. And the dangerous flow of water through the bridge piers made passing under the bridge in a boat recklessly foolish. It was said the bridge was "for wise men to pass over, and for fools to pass under." Though those wise men had better not be in a hurry. Since London Bridge was the only bridge across the Thames (in London) until the 19th century, it was often so congested it could take hours to cross.

"An engraving by Claes Visscher showing Old London Bridge in 1616, with what is now Southwark Cathedral in the foreground. The spiked heads of executed criminals can be seen above the Southwark gatehouse." (Thanks again, Wikipedia!)

The black metal structure overhanging the shore in the middle of the picture is a crane for loading garbage barges. And that's right in the middle of the City - that's Canon Street rail bridge in the background.

But back to the riverbank. Suitably gloved up, we were set loose on a section of the Thames foreshore just in front of the Tate Modern, where there's a handy gate in the railings on the embankment and a very comfortable stone staircase that leads right down to the beach. Fiona let us poke around on our own, but did tell us the rules. First and foremost - no digging allowed. Digging would require a Thames Foreshore Permit. And we're not only talking about shovels-and-backhoes kind of digging either. Using any kind of implement to scratch the surface is considered digging, so we were even warned against nudging things around with our feet. Nonetheless, the Port of London Authority did not descend in black helicopters to arrest anyone in our tour.

Fiona encouraged us to grab anything that looked interesting (we'd been warned ahead of time to bring a bag to carry what we collected). And after about twenty minutes she gathered us up and had us lay out our treasures on a few heavy wooden posts sticking up from the riverbed, so she could tell us about what we'd found. That's the great advantage of mudlarking with a pro. You might find something interesting on your own, but would you really be about to identify it? Or understand how interesting it really is?

For instance, would you be able to tell that horrible black boot at the top of the picture is Victorian? It has hob nails in the heels and everything.

The area of shore we were on also once contained a glass bottle factory, so there were quite a few interesting chunks of glass found. I found an odd bit that Fiona thought might be part of the neck of a Codd bottle, named after the brilliantly-baptised Hiram Codd. He invented the Codd bottle for carbonated drinks, and versions of it are still in use today (in Japan, for instance...). The basis of the system is a metal or glass marble that resides in the specially shaped neck of the bottle. When the bottle is filled with a carbonated liquid the pressure inside the bottle forces the marble up against a rubber washer, sealing the bottle. Clever Hiram!

Here's a picture of some rare, intact Codd bottles

My treasure from the morning of mudlarking, including the chunk of Codd bottle (it's about two inches across) a few tiny bits of broken crockery (some with pleasing patterns) and a microscopic piece of pipe stem. Fiona encouraged us to take only a small number of piece away with us.

And so I did.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment