One of the (many) pleasures of this Christmas was that I ended up with a slew of new books to read. Some of these were gifts, and some were my own purchases, because Amazon were doing a "12 Days of Kindle" sale with many many many ebooks on sale for as little as 99p. This meant that in addition to the dead tree books I received from others, I also managed to acquire, er... EIGHT ebooks with which to while away my time. (Though in fairness one of those was sort of a mistake - Curse you One Click Ordering Button!).

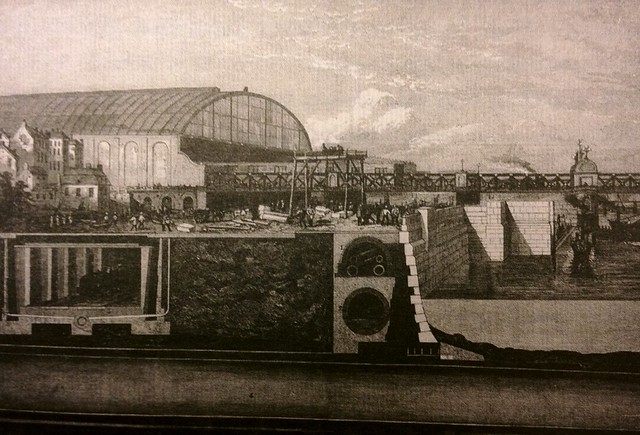

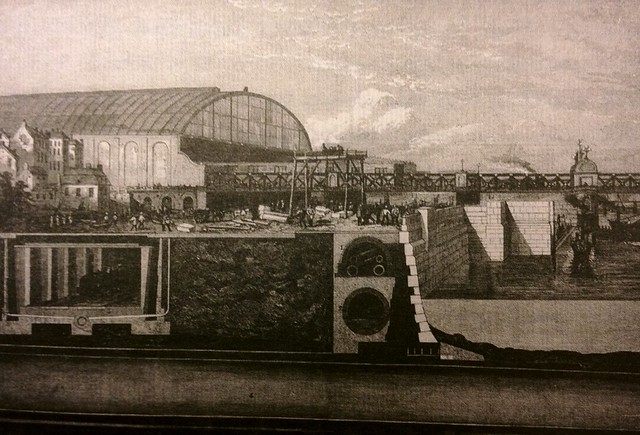

See? River on the right, sewers in the middle, trains on the left. And happy Londoners strolling about on top, without the need for chlorinated sheets or gas masks.

London Under dwells for a while on water mains and gas pipes and electric cables and telephone lines. (London was the first city in the world to locate its entire telephone system underground.) But Ackroyd really gets going when he starts talking about the Tube and the tunnels that contain it, including the tunnels under the Thames. I've already blogged about Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and the first ever tunnel under this or any river (still in use today). I've even already linked to that blog in the very post, so there's no need to bang on about it here anymore.

What I liked most were the chapters on the Underground itself, which was the first underground railway system in the world, opened to the public exactly 148 years ago yesterday, on January 10, 1863. (Happy Birthday Tube!). It's so old that:

The Tube system has evolved continuously since it opened. New tunnels are dug and old ones abandoned, and stations change names, or lines, or are closed completely. The London Transport Museum has an excellent video display about the Tube Map that shows the zillions of iterations it has gone through - in a span of a few minutes you can watch the system grow and change like a living thing. It's mesmerising. (Or is that just me again?) In London Under Ackroyd relates a simultaneously funny and chilling story about the dead South Kentish Town Station, in between Kentish Town and Camden on the Northern Line. Apparently a passenger mistakenly alighted at South Kentish Town when the train was stopped at a red signal. How he managed to get through the doors is not clear. Nor is it explained why he chose to get off at a dark abandoned platform at all. What is said is that he ended up stranded for a week, and was only rescued when a passenger on a passing train noticed the burning advertising posters he set alight as a signal. No wonder people complain about the Northern Line.

Given their naturally spooky nature, the Tube system has its share of ghost stories too. Underground tunnels pass right through many burial grounds and plague pits; deaths occurred in their construction, and murders and suicides have occurred on many lines. Suicide is a constant fact of life in the Tube. Apparently, three attempts are made per week, one if which is successful (though the term"successful" seems an odd one to use in this context). "The most popular time of day is 11:00am, and the most popular venues are King's Cross and Victoria." Every once in a while you'll hear an announcement explaining a delayed train that says something like, "We apologise for the delay to your service, this is due to an earlier person under a train at Chancery Lane." Erg.

All in all, London Under was a good read. It's starts a bit slowly, but ends up giving a lot of fun, evocative facts about the London beneath our (or at least my) feet. How could you not like a book that informs you that the Elgin Marbles were stored for safekeeping during the Blitz in empty tunnels under Aldwych? Or that underground vaults at Bank contain the second-largest hoard of gold bullion in the world? It's not going to change your life, but it might open your eyes a bit.

Interestingly, though it did not appear on any of my various lists, I actually received two copies of the same book: London Under, by Peter Ackroyd. My family know me well - Ackroyd is the author of London: The Biography, an 822 page doorstop of a book that's been weighing down my nightstand for months now. While I've had trouble getting stuck into The Biography (so far it's best viewed as a soporific), London Under proved to be a short, snappy and engaging read. I started it on the plane on the way home, and finished it not long after. This is partly because of its modest length, and partly because it's full of all kinds of the things I love: London, interesting trivia about London in particular, tunnels in general, and the Tube in particular.

It's even got a tunnel on the cover! What's not to love?

Water is an inescapable part of life in London, and the city's underground life is no different. Built on clay, sand and gravel, the entire city is slowly sinking, meaning that the waters that flow beneath it have to be pumped out at a rate of 15,400,000 gallons per day in an effort to keep London's feet dry. London Under starts with a look at the hidden and forgotten wells and waterways that tax those pumps. Wells that used to provide drinking water - some as far back as Roman times - now survive mostly as place names that are largely dissociated from their original purpose. Consider: Clerkenwell, Sadler's Wells, Shadwell, Holywell Street, Bridewell, Camberwell and Stockwell (just down the road from me!). This is one of the joys of London - the fact that something as simple as the name of a tube station can reveal history going back hundreds (if not almost a thousand) years. In Saskatoon a neighbourhood might be called Fairhaven simply because a real estate developer thought it had a nice ring to it. In London Marylebone Road follows the route of the much older Marylebone Lane. And the name "Marylebone" is derived from the name of a church: St. Mary by the bourne (a bourne is a brook). The bourne in question in actually the hidden Tyburn river, which originates in Hampstead and follows the course of the street towards central London and the Thames. (Though of course it's more accurate to say the street follows the course of the Tyburn.)

The rivers of London have been used, abused and bridged for millennia and most have now been covered over and forgotten. There's the aforementioned Tyburn (also of the infamous Tyburn Tree) the Walbrook, Stamford Brook (another tube station), the Neckinger, the engagingly named Wandle (which still survives above ground in parts of south London) and of course the once mighty Fleet. Most exciting of these lost rivers for me is the Effra, which rises in Norwood, south London and passes through Dulwich (I run there!) and Herne Hill (and there!) before entering Brixton where it runs under Brixton Road and near the appropriately named Effra Road. (Effra Road! That's mere steps from my house. I walk it almost every day!) And no wonder another nearby street is called Brixton Water Lane. Apparently the Effra used to be wide enough to support barge traffic, and King Canute once sailed its waters up to Brixton (probably to catch a movie or grab a latté). We've also got Coldharbour Lane and Rush Common, a long skinny stretch of sadly ignored green space that runs along Brixton Road, as if it were the banks of a watercourse, perhaps covered in... rushes. It all makes so much sense.

Map showing watery landmarks in da 'hood

Even more compelling though, are London Under's stories about tunnels. You already know I'm a bit of a fan of bridges and tunnels and such, so it should be no surprise that these bits were my favourite. The story of London's sewers alone could probably support a whole book (though such a book would likely knock London: The Biography out of the park in the Books-To-Fall-Asleep-By game). If there were Roman sewers in London, and there probably were, they have not survived (though some Roman sewers in Rome itself lasted until 1913!). Instead, medieval London's sewers were the open waters of the rivers we just talked about, along with the biggest of London's rivers, the Thames. This was part of the reason that people were so keen to brick over those smaller waterways, though covered sewers and cesspits resulted in distressingly frequent methane explosions. The earliest underground pipes to carry waste in London were built in the thirteenth century (!), but proper brick sewers didn't emerge until the seventeenth.

The hero of London's sewers, though, must surely be Joseph Bazalgate who was the Chief Engineer of the Metropolitan Board of Works in 1858, the summer of what is cringingly known as the "Great Stink". It was at this time that the deteriorating condition of London's then 200-year old sewers, combined with the mass introduction of flush toilets in private homes led to so severe a miasmic funk from the then decidedly brown Thames that drastic measures were needed.

The hero of London's sewers, though, must surely be Joseph Bazalgate who was the Chief Engineer of the Metropolitan Board of Works in 1858, the summer of what is cringingly known as the "Great Stink". It was at this time that the deteriorating condition of London's then 200-year old sewers, combined with the mass introduction of flush toilets in private homes led to so severe a miasmic funk from the then decidedly brown Thames that drastic measures were needed.

"The windows of the Houses or Parliament were covered with sheets soaked in chlorine, but they could not prevent the stench from what Disraeli called, 'a Stygian pool reeking with ineffable and unbearable horror.'" (London Under)

Bazalgate proposed an ambitious system of underground sewers running parallel to the Thames to intercept the, err, waste material before it reached the river and redirect it to the outskirts of the city. There's no word of what the residents of Barking (northeast London) and Crossness (south) thought about having all of London's crap (literally) at their doorsteps, but the plan went ahead. This not only resulted in a much sweeter smelling city, but it also in the reclamation of 22 acres of land from the river and the formation of the Thames Embankment as we know it today. And what runs under that embankment besides big pipes full of The Great Stink? Tube trains in tunnels!

See? River on the right, sewers in the middle, trains on the left. And happy Londoners strolling about on top, without the need for chlorinated sheets or gas masks.

London Under dwells for a while on water mains and gas pipes and electric cables and telephone lines. (London was the first city in the world to locate its entire telephone system underground.) But Ackroyd really gets going when he starts talking about the Tube and the tunnels that contain it, including the tunnels under the Thames. I've already blogged about Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and the first ever tunnel under this or any river (still in use today). I've even already linked to that blog in the very post, so there's no need to bang on about it here anymore.

What I liked most were the chapters on the Underground itself, which was the first underground railway system in the world, opened to the public exactly 148 years ago yesterday, on January 10, 1863. (Happy Birthday Tube!). It's so old that:

"Its first travellers wore top and frock-coats; there are early photographs of horse-drawn hansom cabs parked outside the underground stations. Oscar Wilde was a commuter on these subterranean trains... Charles Dickens and Charles Darwin could both have used the Underground... (and) Jack the Ripper could have travelled on the Underground to Whitechapel."On that first day of service in 1863 trains ran between Paddington and Euston in a tunnel run by the Metropolitan Railway Company. That tunnel, like Brunel's, is still in use today. The first tube trains were driven by steam engines and looked exactly like surface trains, without the benefit of open air to dispel the smoke and fumes they generated. Despite this drawback, the underground railway was a huge success, and many other companies sprang up to produce additional lines and compete with the Metropolitan Railway, which itself served 3,000 passengers a day. Today's system serves 2.7 million daily - 1 billion per year.

The Tube system has evolved continuously since it opened. New tunnels are dug and old ones abandoned, and stations change names, or lines, or are closed completely. The London Transport Museum has an excellent video display about the Tube Map that shows the zillions of iterations it has gone through - in a span of a few minutes you can watch the system grow and change like a living thing. It's mesmerising. (Or is that just me again?) In London Under Ackroyd relates a simultaneously funny and chilling story about the dead South Kentish Town Station, in between Kentish Town and Camden on the Northern Line. Apparently a passenger mistakenly alighted at South Kentish Town when the train was stopped at a red signal. How he managed to get through the doors is not clear. Nor is it explained why he chose to get off at a dark abandoned platform at all. What is said is that he ended up stranded for a week, and was only rescued when a passenger on a passing train noticed the burning advertising posters he set alight as a signal. No wonder people complain about the Northern Line.

Given their naturally spooky nature, the Tube system has its share of ghost stories too. Underground tunnels pass right through many burial grounds and plague pits; deaths occurred in their construction, and murders and suicides have occurred on many lines. Suicide is a constant fact of life in the Tube. Apparently, three attempts are made per week, one if which is successful (though the term"successful" seems an odd one to use in this context). "The most popular time of day is 11:00am, and the most popular venues are King's Cross and Victoria." Every once in a while you'll hear an announcement explaining a delayed train that says something like, "We apologise for the delay to your service, this is due to an earlier person under a train at Chancery Lane." Erg.

All in all, London Under was a good read. It's starts a bit slowly, but ends up giving a lot of fun, evocative facts about the London beneath our (or at least my) feet. How could you not like a book that informs you that the Elgin Marbles were stored for safekeeping during the Blitz in empty tunnels under Aldwych? Or that underground vaults at Bank contain the second-largest hoard of gold bullion in the world? It's not going to change your life, but it might open your eyes a bit.

2 Comments:

Very interesting to me too. That book may end up on my bedside table too...

How about some stories about working at your dream job: The Summer Olympic Games!!

Cheers,

Rob H.

Yes... would love to hear about your job (just like Rob H.). What are you doing, who do you work with, and all the other stuff I know you can make so interesting... so a plea from me too!

Post a Comment