I recently took a short weekend trip to Stratford-on-Avon (definitely NOT to be confused with the Stratford in north London which is, shall we say, a tad rougher around the edges. Though it would be exceedingly amusing to discover how many blue-haired foreign fans of Shakespeare end up hurrying out of the Stratford tube station expecting to see tipsy half-timbered Tudor buildings, tea rooms selling Bakewell tarts and Shakespeare trivets and are instead confronted with shuttered storefronts, kebab shops, and people hawking cheap international phone cards. I bet there are one or two a year, at least…)

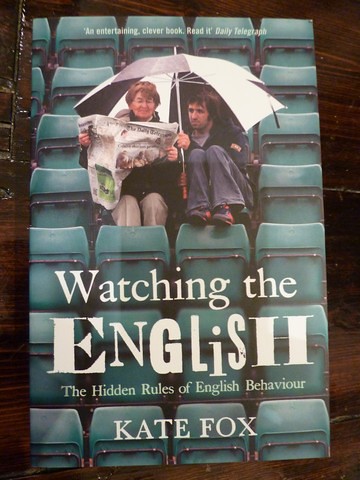

But back to my trip to Shakespeare’s Stratford – I was there mostly to visit a friend who works at the Royal Shakespeare Company, and had a lovely day touring around with him. He showed me all the theatre spaces and also took me the church where Shakespeare is buried, and the building where it’s generally believed he was born. It was a really lovely break from London, and I came away glad for the trip, and well into a book of his that he recommended and loaned me: “Watching the English: The Hidden Rules of English Behaviour” by Kate Fox.

Fox is a social anthropologist who has devoted much of her career to studying the behaviour of her own tribe: the English. In pubs, at race tracks, in shops, on trains and on sidewalks, she has devoted much of her professional life to discovering what she calls “the hidden, unspoken rules of English behaviour, and what those rules tell us about our national identity.” I took to the book instantly, probably because, though I grew up among a lot of English relatives and figured I’d have no trouble at all fitting right in when I arrived, I’ve discovered there are many times when I just want to scream, “Stop being so ENGLISH!” because of the sheer maddening perverseness of it all. Conversely, there are probably an equal number of times when I think, with a little glow of pleasure, “Awww… that’s so ENGLISH!”

It’s a proper academically rigorous book, with footnotes and everything, but the language and writing style is fun and easy to get through, with lots of first-person comments from the author herself. The book is peppered with anecdotes about the research Fox did, and how she went about it. Favourite among these is her story about her hands-on experiment (properly termed “participant observation”) to do with the natural tendency of the English to apologise for almost anything. The section was called, with clinical precision, “Bumping Experiments and the Reflex-Apology Rule” (but honestly, it was an easy read!). Fox’s goal with the experiment was to see how many apologies she could elicit from people she had intentionally bumped into on the street. That is to say, how many people would say “Sorry” to her when she bumped into them.

The same thing happened in another amusing section wherein the author attempts to observe what she calls the “money talk taboo” by deliberately bringing up the awkward topic at dinner parties, even going so far as to ask the hosts, outright, how much their house cost. This made me laugh and cringe at the same time when I read it: Fox trying to screw up the courage to bring up such a forbidden topic, and everyone else’s reaction when she finally managed to get the question out: uneasy coughs, raised eyebrows and sidelong glances across the table – classic signs of an Englishman in high dudgeon.

I think “Watching the English” is really well done. It covers a huge range of topics – conversation, humour, class, home life, work life, travel, dress, food, sex – this book has it all. Fox combs through all these aspects of life and looks at how “Englishness” is displayed in each. And what are the conclusions of the book? What is it that defines “Englishness”? Kate Fox makes her diagnosis that central to the very core of it all is a general sense of unease and awkwardness in any social situation – she called it the English “social dis-ease” and sees it as the root of all the other behaviours she defines as typically English. One way I can describe what I think she’s driving at with this social dis-ease is that stereotypical stammering, awkward Hugh Grant kind of character we’re familiar with from films like “Notting Hill”.

Here are a few of the other traits that Fox singles out as defining “Englishness”:

Class-consciousness: This one is particularly hard for me, as a North-American, to grasp, but the class system is definitely alive and well in England, and everyone brought up here has an innate sense of class-radar that’s always on. Shaw was not kidding around when he wrote “It is impossible for an Englishman to open his mouth without making some other Englishman hate or despise him.” Class determines and is determined by where you live and what kind of house you live in, how you speak, how you dress, where you send your kids to school, who you socialise with and what you do when socialising, which newspapers you read, how and what you eat, in short – everything about how you live. It’s not always obvious, but it’s pretty much always there. One co-worker – definitely a middle class bloke – related a story about having to pull his young son up short because the boy was starting to develop a bit of a “south London” accent – that’s the one that sounds like all vowels mushed together, where “th” becomes “f” or “v” (“nothing” becomes “nuffink”) and where the “t” sound is missing entirely, replaced by a glottal stop. It’s not as complicated as it sounds, you’d know it when you hear it - think early Jamie Oliver. “No, no”, my colleague protested to his 5-year old, “You must pronounce your Ts!”. They start ‘em young.

Moderation can also be observed in things like the English love for “a nice cup of tea and a biscuit”. Honestly, could they not set their sites a bit higher? A mere biscuit? It probably doesn’t even have jam in it, or icing. But then again we “mustn’t have too much of a good thing.”

Fair play: Fox describes this as “a national quasi-religion obsession”, but is quick to point out that it’s not about devising a fake, happy scheme where everyone wins. The English accept that there will be winners and losers, but feel that everyone should be given a fair crack, as long as they follow the rules, don’t cheat, and don’t shirk from duty. And it’s not just about cricket – the sense of fair play shows up in everyday life too, perhaps most famously in the English skill and propensity for queuing (that’s “lining up for stuff” for the North Americans out there). Queuing is practically the national sport, with an unwritten code that everyone understands. Chief among the rules for queuing is that no one shall ever, ever, jump the queue (cut in line). Queue-jumping is roughly on a par with asking someone how much his house cost or possibly with first-degree murder. There are even “invisible queues” in pubs where everyone clusters around the bar to order drinks but everyone in the cluster and the barmen serving knows exactly who’s next in line. And if there’s any doubt, they will automatically defer. My favourite quote from the book about queuing is one Fox credits to George Mikes: “an Englishman, even if he is alone, forms an orderly queue of one.

An orderly queue of quite a bit more than one – outside the Apple Store on Regent Street, waiting for the iPad 2

An orderly queue of quite a bit more than one – outside the Apple Store on Regent Street, waiting for the iPad 2

Modesty: Fox is quick to point out that the English are not necessarily more modest than others, but they are scrupulous about maintaining the appearance of modesty. Thus where someone else will justifiably boast about winning the Olympic gold medal for, oh… archery, say, an Englishman in the same position might be coaxed into admitting that he “does a bit of shooting”. In fact, there’s actually complex reverse-modesty going on here. The more one protests one’s lack of skill or knowledge, the more one can reasonably be expected to be at least a PhD in the subject, if not actually a world-renowned expert. This allows the listener to be simultaneously impressed not just with one’s (presumed) achievements, but also with one’s reluctance to trumpet them.

There are some other traits that Kate Fox writes about in “Watching the English”: courtesy, hypocrisy, empiricism, and something she calls eeyore-ishness, (which is roughly about the English love of a good moan, not to be confused with whinging or whining) but honestly, it’s Sunday afternoon, I’ve got a tax return to do (thank you Revenue Canada), and there could be some important napping in the near future. If this has piqued your interest, I’d recommend getting the book yourself – it really is a good read and has helped me start to understand the motivations behind the quirky, maddening, charming and confusing people with whom I share this tiny island.

And now I think it’s time for a nice cup of tea and a biscuit.

But back to my trip to Shakespeare’s Stratford – I was there mostly to visit a friend who works at the Royal Shakespeare Company, and had a lovely day touring around with him. He showed me all the theatre spaces and also took me the church where Shakespeare is buried, and the building where it’s generally believed he was born. It was a really lovely break from London, and I came away glad for the trip, and well into a book of his that he recommended and loaned me: “Watching the English: The Hidden Rules of English Behaviour” by Kate Fox.

Fox is a social anthropologist who has devoted much of her career to studying the behaviour of her own tribe: the English. In pubs, at race tracks, in shops, on trains and on sidewalks, she has devoted much of her professional life to discovering what she calls “the hidden, unspoken rules of English behaviour, and what those rules tell us about our national identity.” I took to the book instantly, probably because, though I grew up among a lot of English relatives and figured I’d have no trouble at all fitting right in when I arrived, I’ve discovered there are many times when I just want to scream, “Stop being so ENGLISH!” because of the sheer maddening perverseness of it all. Conversely, there are probably an equal number of times when I think, with a little glow of pleasure, “Awww… that’s so ENGLISH!”

It’s a proper academically rigorous book, with footnotes and everything, but the language and writing style is fun and easy to get through, with lots of first-person comments from the author herself. The book is peppered with anecdotes about the research Fox did, and how she went about it. Favourite among these is her story about her hands-on experiment (properly termed “participant observation”) to do with the natural tendency of the English to apologise for almost anything. The section was called, with clinical precision, “Bumping Experiments and the Reflex-Apology Rule” (but honestly, it was an easy read!). Fox’s goal with the experiment was to see how many apologies she could elicit from people she had intentionally bumped into on the street. That is to say, how many people would say “Sorry” to her when she bumped into them.

“My bumping got off to a rather poor start. The first few bumps were technically successful, in that I managed to make them seem coincidentally accidental, but I kept messing up the experiment by blurting out an apology before the other person had a chance to speak. As usual, this turned out to be a test of my own Englishness: I found that I could not bump into someone, however gently, without automatically saying “sorry”. After several false starts, I finally managed to control my knee-jerk apologies by biting my lip – firmly and rather painfully – as I did the bumps.”Classic. I loved how the author struggles with her own instincts in trying to step out of herself long enough to try to be an impassioned observer. It seems much more interesting, or at least different, than reading about some sociologist living in a mud hut and trying to “go native”.

The same thing happened in another amusing section wherein the author attempts to observe what she calls the “money talk taboo” by deliberately bringing up the awkward topic at dinner parties, even going so far as to ask the hosts, outright, how much their house cost. This made me laugh and cringe at the same time when I read it: Fox trying to screw up the courage to bring up such a forbidden topic, and everyone else’s reaction when she finally managed to get the question out: uneasy coughs, raised eyebrows and sidelong glances across the table – classic signs of an Englishman in high dudgeon.

I think “Watching the English” is really well done. It covers a huge range of topics – conversation, humour, class, home life, work life, travel, dress, food, sex – this book has it all. Fox combs through all these aspects of life and looks at how “Englishness” is displayed in each. And what are the conclusions of the book? What is it that defines “Englishness”? Kate Fox makes her diagnosis that central to the very core of it all is a general sense of unease and awkwardness in any social situation – she called it the English “social dis-ease” and sees it as the root of all the other behaviours she defines as typically English. One way I can describe what I think she’s driving at with this social dis-ease is that stereotypical stammering, awkward Hugh Grant kind of character we’re familiar with from films like “Notting Hill”.

Here are a few of the other traits that Fox singles out as defining “Englishness”:

Humour: The English sense of humour is justifiably renowned. Fox sees it as a way of coping with all those awkward interactions required when one is faced with something so daunting as other people. It’s like an antidote, and it’s everywhere. “In other cultures, there is ‘a time and place’ for humour: among the English it is a constant…” And like any muscle that gets a lot of exercise, the English sense of humour is positively Schwarzenegger-like. For instance, the comedy shows on English tv are smarter and funnier than anything I’ve seen elsewhere. The BBC show “QI” alone is really worth a whole blog post, and this is, after all, the home of “Monty Python” and “Fawlty Towers”. But beyond staged funny stuff like television it really is true that everyday encounters with anyone will often lead to a small, funny exchange of some kind. For the English humour is a reflex, like breathing.

Class-consciousness: This one is particularly hard for me, as a North-American, to grasp, but the class system is definitely alive and well in England, and everyone brought up here has an innate sense of class-radar that’s always on. Shaw was not kidding around when he wrote “It is impossible for an Englishman to open his mouth without making some other Englishman hate or despise him.” Class determines and is determined by where you live and what kind of house you live in, how you speak, how you dress, where you send your kids to school, who you socialise with and what you do when socialising, which newspapers you read, how and what you eat, in short – everything about how you live. It’s not always obvious, but it’s pretty much always there. One co-worker – definitely a middle class bloke – related a story about having to pull his young son up short because the boy was starting to develop a bit of a “south London” accent – that’s the one that sounds like all vowels mushed together, where “th” becomes “f” or “v” (“nothing” becomes “nuffink”) and where the “t” sound is missing entirely, replaced by a glottal stop. It’s not as complicated as it sounds, you’d know it when you hear it - think early Jamie Oliver. “No, no”, my colleague protested to his 5-year old, “You must pronounce your Ts!”. They start ‘em young.

“What is distinctive about the English class system is (a) the degree to which our class (and/or class anxiety) determines our taste, behaviour, judgements and interactions; (b) the fact that class is not judged at all on wealth, and very little on occupation, but purely on non-economic indicators such as speech, manner, taste and lifestyle choices; (c) acute sensitivity of our on-board class radar systems; and (d) our denial of all this and coy squeamishness about class…”Moderation: “What do we want? GRADUAL CHANGE! When do we want it? IN DUE COURSE!”. (See, there’s the sense of humour again.) It’s about avoiding extremes and excesses and certainly about never, ever making a fuss. I encountered this at work one day when a guy cut his finger fairly badly and came up to the office for some help. Rather than simply announcing he was hurt and needed a bit of first aid - far too dramatic - he mumbled past the bleeding finger in his mouth, repeatedly asking for a particular co-worker who eventually spirited him off to deal with the matter in private. The rest of us were left wondering if we were dealing with something on the order of a bad paper cut, or whether we should be pawing through piles of sawdust for a missing digit. Though of course no one asked because we didn’t want to make a fuss.

Moderation can also be observed in things like the English love for “a nice cup of tea and a biscuit”. Honestly, could they not set their sites a bit higher? A mere biscuit? It probably doesn’t even have jam in it, or icing. But then again we “mustn’t have too much of a good thing.”

Fair play: Fox describes this as “a national quasi-religion obsession”, but is quick to point out that it’s not about devising a fake, happy scheme where everyone wins. The English accept that there will be winners and losers, but feel that everyone should be given a fair crack, as long as they follow the rules, don’t cheat, and don’t shirk from duty. And it’s not just about cricket – the sense of fair play shows up in everyday life too, perhaps most famously in the English skill and propensity for queuing (that’s “lining up for stuff” for the North Americans out there). Queuing is practically the national sport, with an unwritten code that everyone understands. Chief among the rules for queuing is that no one shall ever, ever, jump the queue (cut in line). Queue-jumping is roughly on a par with asking someone how much his house cost or possibly with first-degree murder. There are even “invisible queues” in pubs where everyone clusters around the bar to order drinks but everyone in the cluster and the barmen serving knows exactly who’s next in line. And if there’s any doubt, they will automatically defer. My favourite quote from the book about queuing is one Fox credits to George Mikes: “an Englishman, even if he is alone, forms an orderly queue of one.

An orderly queue of quite a bit more than one – outside the Apple Store on Regent Street, waiting for the iPad 2

An orderly queue of quite a bit more than one – outside the Apple Store on Regent Street, waiting for the iPad 2Modesty: Fox is quick to point out that the English are not necessarily more modest than others, but they are scrupulous about maintaining the appearance of modesty. Thus where someone else will justifiably boast about winning the Olympic gold medal for, oh… archery, say, an Englishman in the same position might be coaxed into admitting that he “does a bit of shooting”. In fact, there’s actually complex reverse-modesty going on here. The more one protests one’s lack of skill or knowledge, the more one can reasonably be expected to be at least a PhD in the subject, if not actually a world-renowned expert. This allows the listener to be simultaneously impressed not just with one’s (presumed) achievements, but also with one’s reluctance to trumpet them.

There are some other traits that Kate Fox writes about in “Watching the English”: courtesy, hypocrisy, empiricism, and something she calls eeyore-ishness, (which is roughly about the English love of a good moan, not to be confused with whinging or whining) but honestly, it’s Sunday afternoon, I’ve got a tax return to do (thank you Revenue Canada), and there could be some important napping in the near future. If this has piqued your interest, I’d recommend getting the book yourself – it really is a good read and has helped me start to understand the motivations behind the quirky, maddening, charming and confusing people with whom I share this tiny island.

And now I think it’s time for a nice cup of tea and a biscuit.

3 Comments:

Sounds most interesting. And now that I have my beloved Kindle... ;)

Another you might favor is Bill Bryson's "The Mother Tongue. Likewise fascinating, and also hilarious.

This will be fun. Maybe make better sense of my kin.

I am so thrilled that you started a new blog to go with the new chapter in your life! I followed your previous travel blog with great interest.

I have now rushed to the libray and taken this book out on your advice! Very excited to read it as Bill Bryson's (mentioned above)Notes from a Small Island is one of my fav books (cannot read it on public transport as I can't contain the laughter).

Keepp up the great blogging - I now have my Mom hooked and she is also reading back "editions" of your travel blog

Jessica

Post a Comment