It’s time to discover another typically Brit treat that will probably be new to anyone who hasn’t been over here: Jaffa Cakes!

Jaffa Cakes are produced by McVitie and Price (McVitie’s also manufacturer another local favourite, the sublime dark chocolate covered Hobnob) and were first introduced in 1927. For reasons which will shortly become clear, they’re named after Jaffa oranges. Jaffa Cakes are not precisely cakes and not precisely biscuits. They’re the size of a biscuit, and tend to be consumed in the same way, and are found in the biscuit section of the grocery store. However, they are most certainly composed primarily of cake, or, to use the correct local term “sponge”. (More on the cake vs. biscuit debate later.)

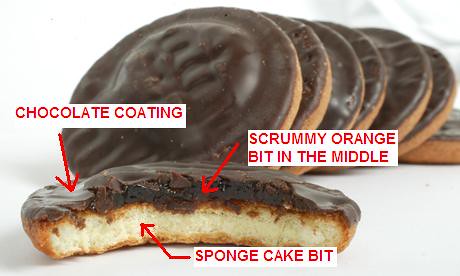

A 2-1/8” (54mm) diameter circle of sponge forms the base of the common Jaffa Cake, and the top is covered in a thin layer of dark chocolate, which is not a bad start. But it’s what's in between the sponge and the chocolate where the magic happens. Sitting atop the sponge is a thick layer of what is best described as “scrummy orange stuff”, a sort of thick orange flavoured jelly. It’s that scrummy orange stuff that makes the Jaffa Cake great.

They’re soft and a bit chewy and quite chocolately, with just the right the hit of orange. And they’re really good with coffee, or a nice cup of tea. Also, they are really good consumed one after another after another after another until the end of the package is reached with surprising haste and no small amount of regret, both at the realization that you’ve just eaten an entire package of Jaffa Cakes, and at the realization that there are no more Jaffa Cakes.

However, Jaffa Cakes are not perfect. For one thing, it bothers me that the scrummy orange bit only covers a portion of the top of the cake – a mere 1-1/2” in diameter. Also, it’s distressingly rare to get a truly fresh Jaffa Cake, meaning that the sponge on the bottom is usually somewhere between “a bit stale” and “dentally challenging”. I’ve had some good luck with one particular knock-off non-McVitie imitator, which defiantly covers almost the whole top with scrumminess and which also seem to manage to stay fresher longer (likely with the addition of alarming chemicals, but who’s kidding who? That scrummy orange stuff is probably mostly chemicals too. Though encouragingly the package does actually list concentrated orange juice as an ingredient).

Some might consider the oranginess of Jaffa Cakes to be a defining characteristic (Patrick, I’m talking to you). But McVitie’s have made special edition flavours in the past, including lemon-lime, strawberry and black currant (So there!). Personally, I’m a fan of the knock-off raspberry Jaffa Cakes that were available at the miserable grocery store I used to go to when I lived up in Arsenal. Arsenal did not have a lot going for it, but those Jaffa Cakes certainly helped. (As did the Happening Bagel Bakery, which was across the street from the miserable grocery store, and which did the best bagels I’ve had in London. It also stayed open to all hours so that if someone happened to be coming home late after a hash run and was feeling slightly tipsy, and kinda hungry, and certainly lacking in self restraint, someone could get a hot samosa or sausage roll to consume while wending his or her way home from the tube station.)

And what about the cake vs. biscuit controversy I alluded to earlier? Here’s the scoop, straight from Wikipedia:

By the way, Gustav agrees that Jaffa Cakes are certainly cakes and not biscuits, and I think we can assume he is a man who knows a thing or two about Jaffa Cakes.

And there you have it, the low-down on another native delicacy that’s become part of my life here in London. And for the record, I would like it known that I only ate THREE Jaffa Cakes the whole time I was writing this, which I think is a world record for Least Number Of Jaffa Cakes Consumed While Composing A Blog Post About Jaffa Cakes.

P.S. In researching this blog post (no, I don’t just make this stuff up. Well, at least not ALL of it) I came across a website that I feel like sharing. The writing style reminds me a bit of my own, if I were to devote myself exclusively to tea-and-biscuit related blogging. It’s quirky, it’s fun, and if you want the warts-and-all reviews for just about every biscuit that you can find on the shelves in the UK, have a look at A Nice Cup of Tea and a Sit Down, where there mission is, and I quote “Well I think we should all sit down and have a nice cup of tea, and some biscuits, nice ones mind you. Oh and some cake would be nice as well. Lovely.”

Jaffa Cakes are produced by McVitie and Price (McVitie’s also manufacturer another local favourite, the sublime dark chocolate covered Hobnob) and were first introduced in 1927. For reasons which will shortly become clear, they’re named after Jaffa oranges. Jaffa Cakes are not precisely cakes and not precisely biscuits. They’re the size of a biscuit, and tend to be consumed in the same way, and are found in the biscuit section of the grocery store. However, they are most certainly composed primarily of cake, or, to use the correct local term “sponge”. (More on the cake vs. biscuit debate later.)

A 2-1/8” (54mm) diameter circle of sponge forms the base of the common Jaffa Cake, and the top is covered in a thin layer of dark chocolate, which is not a bad start. But it’s what's in between the sponge and the chocolate where the magic happens. Sitting atop the sponge is a thick layer of what is best described as “scrummy orange stuff”, a sort of thick orange flavoured jelly. It’s that scrummy orange stuff that makes the Jaffa Cake great.

However, Jaffa Cakes are not perfect. For one thing, it bothers me that the scrummy orange bit only covers a portion of the top of the cake – a mere 1-1/2” in diameter. Also, it’s distressingly rare to get a truly fresh Jaffa Cake, meaning that the sponge on the bottom is usually somewhere between “a bit stale” and “dentally challenging”. I’ve had some good luck with one particular knock-off non-McVitie imitator, which defiantly covers almost the whole top with scrumminess and which also seem to manage to stay fresher longer (likely with the addition of alarming chemicals, but who’s kidding who? That scrummy orange stuff is probably mostly chemicals too. Though encouragingly the package does actually list concentrated orange juice as an ingredient).

Some might consider the oranginess of Jaffa Cakes to be a defining characteristic (Patrick, I’m talking to you). But McVitie’s have made special edition flavours in the past, including lemon-lime, strawberry and black currant (So there!). Personally, I’m a fan of the knock-off raspberry Jaffa Cakes that were available at the miserable grocery store I used to go to when I lived up in Arsenal. Arsenal did not have a lot going for it, but those Jaffa Cakes certainly helped. (As did the Happening Bagel Bakery, which was across the street from the miserable grocery store, and which did the best bagels I’ve had in London. It also stayed open to all hours so that if someone happened to be coming home late after a hash run and was feeling slightly tipsy, and kinda hungry, and certainly lacking in self restraint, someone could get a hot samosa or sausage roll to consume while wending his or her way home from the tube station.)

And what about the cake vs. biscuit controversy I alluded to earlier? Here’s the scoop, straight from Wikipedia:

In the UK, value added tax is payable on chocolate covered biscuits, but not on chocolate covered cakes. McVities defended its classification of Jaffa Cakes as cakes in court, producing a 12" (30 cm) Jaffa Cake to illustrate that its Jaffa Cakes were simply miniature cakes. McVities argued that a distinction between cakes and biscuits is, among other things, that biscuits would normally be expected to go soft when stale, whereas cakes would normally be expected to go hard. It was demonstrated to the Tribunal that Jaffa Cakes become hard when stale. Other factors taken into account by the Chairman, Potter QC, included the name, ingredients, texture, size, packaging, marketing, presentation, appeal to children, and manufacturing process. Potter ruled that the Jaffa Cake is a cake. McVities therefore won the case and VAT is not paid on Jaffa Cakes in the UKSo there you have it – no VAT on Jaffa Cakes. One more reason to love them. (And as an aside, I wonder how that tribunal Chairman, Potter QC, ended up getting the Jaffa Cake file? Was it a punishment or a reward?)

Finally, one last bit of Jaffa Cake trivia. I bet you can’t guess the world record for greatest number of Jaffa Cakes eaten in one minute. Twenty? Thirty? Fifty? Nope. It’s… eight. And for a long time it wasn’t even that. For a long time, the record was a lousy four. I’m not kidding. You’re probably thinking, “Wait a minute. They’re only 2” across, and the most anyone could get down was four in a minute? I’ve never even tried one before and I bet I could do better than that.” Not so fast. It turns out the rules set out by the Guinness World Records people are quite strict. You can only eat one Jaffa cake at the time and you must show a completely empty mouth before starting to eat the next one. And, most importantly, you can’t drink anything during the minute. I think it’s the no drinking thing that flummoxes most people. However, Gustav Shulz, a German student studying English in the UK was undaunted by the challenge, and thus I am able to bring you this video:

By the way, Gustav agrees that Jaffa Cakes are certainly cakes and not biscuits, and I think we can assume he is a man who knows a thing or two about Jaffa Cakes.

And there you have it, the low-down on another native delicacy that’s become part of my life here in London. And for the record, I would like it known that I only ate THREE Jaffa Cakes the whole time I was writing this, which I think is a world record for Least Number Of Jaffa Cakes Consumed While Composing A Blog Post About Jaffa Cakes.

P.S. In researching this blog post (no, I don’t just make this stuff up. Well, at least not ALL of it) I came across a website that I feel like sharing. The writing style reminds me a bit of my own, if I were to devote myself exclusively to tea-and-biscuit related blogging. It’s quirky, it’s fun, and if you want the warts-and-all reviews for just about every biscuit that you can find on the shelves in the UK, have a look at A Nice Cup of Tea and a Sit Down, where there mission is, and I quote “Well I think we should all sit down and have a nice cup of tea, and some biscuits, nice ones mind you. Oh and some cake would be nice as well. Lovely.”

An orderly queue of quite a bit more than one – outside the Apple Store on Regent Street, waiting for the iPad 2

An orderly queue of quite a bit more than one – outside the Apple Store on Regent Street, waiting for the iPad 2