There is a lot to say about Australia and I thoroughly enjoyed my time there. It turns out I’ve got a bit of a network of Aussie friends, many of whom are surprisingly willing to house me in their spare rooms or buy me dinner or chauffeur me around the country for days on end, which is both humbling and excellent. Now that I think about it, I guess I also may have a gang like that in Athens, and in New York City and probably in a few other places I can’t think of right now. This is one of the many fringe benefits of doing the kind of work I do. You end up with a widely scattered network of people you’ve been through the wars with who will almost always be happy to stand you a few drinks and give you a place to lay your head.

There's lots to say about Australia but for today we will concentrate on an iconic symbol of Sydney in particular and Australia in general, and one which Astute Go Stay Work Play Live Readers will be supremely unsurprised to learn captured my attention quite thoroughly: the Sydney Harbour Bridge!

There’s now a fairly extensive back-catalogue of bridge blogs, so truly devoted fans should have a troll through the archives for fond remembrances of the Golden Gate, Tower Bridge, the Rolling Bridge, Iron Bridge and the Clifton Suspension Bridge. Ah, bridges. It’s no secret I’m fond of a bit of mechanical or sturctural engineering in general, but bridges in particular are a firm favourite. In buildings and tunnels the engineering is there but it’s mostly hidden. Bridges are where engineers get to show off. It’s like they're shouting, “Look what we can make because we know how stuff works!”

(Standby for mandatory bridge backstory, because I actually bought a book!)

European settlement of Australia started with the arrival of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove on January 26, 1788, and by the time the last convict ship docked in 1840, Sydney was a thriving community on both the north and south sides of the harbour. The more the city grew, the more inconvenient the 50km trip around the harbour, or across by ferry, became. There were many proposals to link Sydney’s two halves, including a pontoon bridge, tram tunnel and even a earthwork causeway. In 1900 the New South Wales government formally advertised for tenders for the design and construction of a bridge but that project was scrapped after a change in government, despite having attracted twelve submissions over two rounds of tenders. It wasn’t until 1922 that legislation was finally passed to enable construction.

In the interim, an Australian engineer named John Bradfield was named Chief Engineer Metropolitan Railway Construction and Sydney Harbour Bridge. Bradfield spent several years traveling the world studying underground railways and long span bridges at the request of the New South Wales government. (It's like we’re we’re soulmates, Bradfield and I, except the government of New South Wales does not pay me to travel the world blogging about tunnels and bridges. I pay for that myself. However, any and all donations are gratefully accepted.) Bradfield's initial inclinations were towards a cantilever bridge design, but during his travels, he visited the gorgeously arched Hell’s Gate Bridge in New York, and the twice-failed cantilever bridge in Quebec and at the last minute allowed submission of arched bridge designs - mostly, I suspect, because he calculated it would cost £400,000 less.

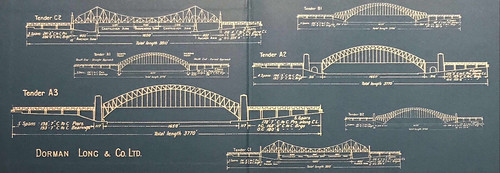

Whatever the reason, the proposal that eventually won out was the now-iconic design from Dorman Long & Co. from Middlesborough in the UK. Construction began in 1923 and the bridge was finally opened to traffic in 1932. Being an arch, the whole enormous load of the bridge itself (the arch alone weighs 39,00 tons) is supported where the bottoms of the arch rest on giant main bearings on the north and south shores. Each bearing is actually a huge hinge that allows for the expansion and contraction of the arch’s steelwork - in high temperatures the overall height can increase by as much as 180mm. Also, the arch itself was cleverly constructed with no supporting falsework underneath! Moving creeper cranes assembled the sections of the arch ahead of themselves, advancing as each was completed. The whole business was prevented from collapsing into the harbour by 128 heavy restraint cables on each side, which were anchored in tunnels in the sandstone.

But enough of bridge history - even though I could go on for at least three more posts about the bridge and its construction and the 6,000,000 steel rivets that hold it together, and how I find it disturbing that the top chord of the arch doesn’t appear to anchor into anything very much. (Which prompted a short conversation and series of back-of-the-cocktail napkin sketches while sitting at the aforementioned Opera Bar and almost culminated in an email to one of the two different structural engineers I met on this gig, until Nick and I decided we’d pretty much figured it out.) Nope, no more about the history and engineering of the bridge - let’s get on with my up close and personal encounters with the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

First, I got driven across the bridge, and as a pedestrian I visited the southeast pylon, which now houses a nice little museum and gives you access to the lookout platform at the top of the tower for some pretty impressive views of the harbour.

But wait, there’s more! It’s also possible to experience the Sydney Harbour Bridge in a particular and unique way: by climbing right over the top! BridgeClimb has been operating since 1998 and allows visitors to climb up through the structure of the bridge and walk along the top of the arch, right to the highest point. This activity was recommended to me by two (very) different people, so despite the hefty price ($303 Australian for the standard three hour experience!) I decided this was a chance not to be missed.

The BridgeClimb did not disappoint. It was a three-hour experience that I prepared for with a proper Aussie breakfast of smashed avocado and poached egg on toast and a flat white (If you think Hackney is a hotbed of smashed avocado on toast, think again. They can’t even hold Sydney’s coat in that department. It’s inescapable. I’m pretty sure if I’d gone to McDonald’s I could have ordered a McAvoSmash.) Unsurprisingly, there’s a fairly extensive health and safety briefing when you first arrive. This is reassuring, since the summit of the bridge is 134m above sea level and takes you over eight active lanes of traffic and a couple of working rail lines. The potential for mayhem is, shall we say, significant.

Everyone in my group of seven was assigned a fetching grey and blue jumpsuit. The colours are designed to blend in with the bridge and be less distracting to motorists, but I predict they will not be appearing on a fashion runway near you anytime soon. We were also instructed to leave everything in pockets behind: no loose change, no mobile phones, no watches, no cameras. Sunglasses were allowed, but they were tethered to the jumpsuits. We were also assigned a waist harness safety belt with a sliding tether line, a fleece jacket in case it got cold, a handkerchief, a yours-to-keep-just-for-playing Sydney Bridge Climb baseball cap, and a radio headset to be able to hear our guide, whose name might have been Brian.

Brian (or was it Brad?) ran us through a sort of BridgeClimb simulator set of stairs, ladders and catwalks that demonstrated how the continuous safety line worked. (I suspect I was the only one in the group who found the rigging of the safety system just a bit fascinating.) Then we were off to clip in and walk along underside of the roadway and up through the southeast pylon before climbing over the arch itself. Even though the elevation gain was large, it was a comfortable climb. We walked over the actual upper chord of the arch, on catwalks laid on top of the steelwork so the incline was fairly gentle. Brian (possibly Bruce) stopped at key points and chatted to us in the way of experienced tour guides - knowledgeable, peppered with well-worn jokes, slightly world-weary, but still charming. He knew a lot about the bridge, and graciously tolerated my unusual fascination with the stainless steel brackets and anchor system for the continuous safety line that runs throughout the catwalk system.

I said no cameras or phones were allowed, but Brian (Brent?) had a special (tethered) camera and we stopped at several points along the way for photo ops. Naturally, BridgeClimb were happy to take more of my money to have a couple of photos provided at the end of the experience, which is why I can show you this:

We finally made it to the very top, where there is a very very small platform that occasionally hosts special events like weddings or tiny expensive parties or those annoying segments on local television morning shows.

By the time it was all over three hours had elapsed, which coincided neatly with the arrival at a nearby pub of my two hosts for a well-deserved beer and lunch. The Australian Heritage Hotel is another Sydney icon, where I was able to sample the famous Coat of Arms pizza - featuring emu meat on one half and kangaroo meat on the other! This allows me to segue neatly into this fun but utterly unsupported fact I heard somewhere: Australians are the only people that eat both the animals on their coat of arms. Also, it's popularly believed that the reason the kangaroo and the emu are featured on the coat of arms is because neither animal can go backwards, which is supposed to be a metaphor for something noble, though of course if a kangaroo or an emu wants to retreat from something clearly all they need to do is turn around and run away like everything else on the planet.

I was feeling pretty smug about my Australia experience by this point - climbed iconic bridge, ate iconic animals, had a nice beer - tick, tick, tick. That was to become the theme for my visit, as you’ll learn in weeks to come. So stay tuned for more kangaroos and associated odd animals, more engineering, more smashed avocado, a surfeit of ridiculously beautiful beaches, and an evening that turned out to be so quintessentially Australian it may as well have been scripted. Advance, Australia Fair!

There's lots to say about Australia but for today we will concentrate on an iconic symbol of Sydney in particular and Australia in general, and one which Astute Go Stay Work Play Live Readers will be supremely unsurprised to learn captured my attention quite thoroughly: the Sydney Harbour Bridge!

Here it is in twilight, as seen from the very charming Opera Bar, just across Circular Quay at the foot of the equally iconic Sydney Opera House.

(Standby for mandatory bridge backstory, because I actually bought a book!)

European settlement of Australia started with the arrival of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove on January 26, 1788, and by the time the last convict ship docked in 1840, Sydney was a thriving community on both the north and south sides of the harbour. The more the city grew, the more inconvenient the 50km trip around the harbour, or across by ferry, became. There were many proposals to link Sydney’s two halves, including a pontoon bridge, tram tunnel and even a earthwork causeway. In 1900 the New South Wales government formally advertised for tenders for the design and construction of a bridge but that project was scrapped after a change in government, despite having attracted twelve submissions over two rounds of tenders. It wasn’t until 1922 that legislation was finally passed to enable construction.

In the interim, an Australian engineer named John Bradfield was named Chief Engineer Metropolitan Railway Construction and Sydney Harbour Bridge. Bradfield spent several years traveling the world studying underground railways and long span bridges at the request of the New South Wales government. (It's like we’re we’re soulmates, Bradfield and I, except the government of New South Wales does not pay me to travel the world blogging about tunnels and bridges. I pay for that myself. However, any and all donations are gratefully accepted.) Bradfield's initial inclinations were towards a cantilever bridge design, but during his travels, he visited the gorgeously arched Hell’s Gate Bridge in New York, and the twice-failed cantilever bridge in Quebec and at the last minute allowed submission of arched bridge designs - mostly, I suspect, because he calculated it would cost £400,000 less.

Tender C1 and C2 are cantilever bridges. The rest are through-arch designs. So-named because the roadway goes through the arch as opposed to passing over it (like this other famous arch bridge).

Once each side of the arch was complete the cables were gradually loosened over the course of three and a half weeks before the two sides eventually met. And you notice how the granite pylon towers at the ends of the bridge aren’t there yet? That’s because they have no structural purpose - they’re simply to give better visual balance to the bridge. Bradfield was apparently fond of quoting John Ruskin on that score: “Life without industry is guilt, and industry without art is brutality.”

First, I got driven across the bridge, and as a pedestrian I visited the southeast pylon, which now houses a nice little museum and gives you access to the lookout platform at the top of the tower for some pretty impressive views of the harbour.

Mmmm… steel trusses!

Yes, the pylon lookout is a pretty good way to appreciate the harbour and the bridge.

The BridgeClimb did not disappoint. It was a three-hour experience that I prepared for with a proper Aussie breakfast of smashed avocado and poached egg on toast and a flat white (If you think Hackney is a hotbed of smashed avocado on toast, think again. They can’t even hold Sydney’s coat in that department. It’s inescapable. I’m pretty sure if I’d gone to McDonald’s I could have ordered a McAvoSmash.) Unsurprisingly, there’s a fairly extensive health and safety briefing when you first arrive. This is reassuring, since the summit of the bridge is 134m above sea level and takes you over eight active lanes of traffic and a couple of working rail lines. The potential for mayhem is, shall we say, significant.

Everyone in my group of seven was assigned a fetching grey and blue jumpsuit. The colours are designed to blend in with the bridge and be less distracting to motorists, but I predict they will not be appearing on a fashion runway near you anytime soon. We were also instructed to leave everything in pockets behind: no loose change, no mobile phones, no watches, no cameras. Sunglasses were allowed, but they were tethered to the jumpsuits. We were also assigned a waist harness safety belt with a sliding tether line, a fleece jacket in case it got cold, a handkerchief, a yours-to-keep-just-for-playing Sydney Bridge Climb baseball cap, and a radio headset to be able to hear our guide, whose name might have been Brian.

Brian (or was it Brad?) ran us through a sort of BridgeClimb simulator set of stairs, ladders and catwalks that demonstrated how the continuous safety line worked. (I suspect I was the only one in the group who found the rigging of the safety system just a bit fascinating.) Then we were off to clip in and walk along underside of the roadway and up through the southeast pylon before climbing over the arch itself. Even though the elevation gain was large, it was a comfortable climb. We walked over the actual upper chord of the arch, on catwalks laid on top of the steelwork so the incline was fairly gentle. Brian (possibly Bruce) stopped at key points and chatted to us in the way of experienced tour guides - knowledgeable, peppered with well-worn jokes, slightly world-weary, but still charming. He knew a lot about the bridge, and graciously tolerated my unusual fascination with the stainless steel brackets and anchor system for the continuous safety line that runs throughout the catwalk system.

I said no cameras or phones were allowed, but Brian (Brent?) had a special (tethered) camera and we stopped at several points along the way for photo ops. Naturally, BridgeClimb were happy to take more of my money to have a couple of photos provided at the end of the experience, which is why I can show you this:

Everyone got this cheesy group photo.

And here’s me near the top, with Circular Quay and the Opera House in the background. (Can I also add that this photo in the flattering grey jumpsuit makes it look like I’ve eaten at lot more than my fair share of smashed avocado but really it’s just that the jumpsuit was roomy and the wind was at my back. I promise I didn't actually come home from Indonesian looking like the Michelin Man.)

One more photo at the summit before the climb down.

Good pizza. Though as with most exotic meat, it didn’t really have a distinctive flavour. I am, however, happy to say it didn’t really taste like chicken.