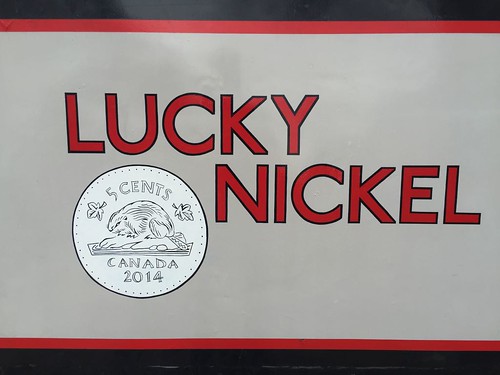

It’s an exciting time here at Go Stay Work Play Live World Headquarters, aboard the "Lucky Nickel". This week, I engaged the services of a talented young woman to paint the name and logo on the side of the boat! Astute Go Stay Work Play readers will recall that when I bought the boat it was named “Dragonfly”, which one might think is a nice name for a boat. And if one did think that one would certainly not be alone in one's thinking because a quick search reveals that there are over a hundred boats registered in the UK called “Dragonfly” or some derivative of that. It is surely one of the most common boat names in the country. So it didn’t take me long to decide that along with repainting, my boat was going to be renamed, and I settled on the new name more than six months ago. Sure, there's a superstition about it being bad luck to change the name of a boat, but I hold no truck with such things. Besides, records that came with the boat indicate that it started life as the “Lisa Jane” and was changed to "Dragonfly" at some point along the way, so really the damage was already done. Also there’s a school of thought that if you’re going to change the name you should do it when the boat is out of the water being painted, which I did, so I think I’m covered.

The question then became one of how to get the new name properly displayed on the boat. I’ve been on the canals full time for more than two months now I’m a little surprised at how many boats I see with no name visible at all. I find this odd and a bit sad. I suppose different boatowners have different priorities but honestly, have some pride, people! For a long time I’d planned to simply have a custom vinyl sticker created from an online company like this one. It seemed like a reasonably economical way of achieving the effect I was looking for, and they even promised they could take a digital image file of the nickel and create a sticker of that, along with the lettering. Job done, I thought.

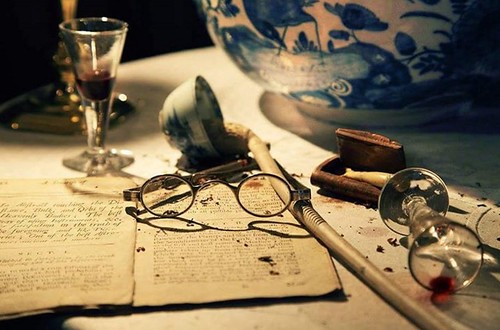

First, though, let’s have a little sidebar and delve into the rich and colourful history surrounding the painting and decoration of narrowboats. And when I say “colourful history” I am definitely not speaking metaphorically. Traditionally, working narrowboats operated and inhabited by bargemen and their families were be heavily decorated in what’s come to be known as the “Roses and Castles” style, which AGSWPLRs might suspect runs heavily to… er… roses and castles. And of course they’d be right.

At the peak of the working canal system - when narrowboats moved the raw materials and products of the Industrial Age along England’s canals, most bargemen were well-paid enough to hire on help and keep their families on dry land in canal side cottages. However, the arrival of the railway brought a new way of moving cargo and a consequent decrease in the demand for and the earnings of bargemen. As a result, many a bargeman was forced to give up his paid help and move his entire family into the cramped and dirty cabin at the end of his boat. This had the twin advantage of reducing living costs and providing free labour to help in working the boats. But life with no fixed address made it difficult to keep children in school or develop community ties, and barge families gradually came to been seen as “apart” from normal society.

Heavily decorated boats are not as common as they once were, but there is still a significant part of the boating community that carries on the Roses and Castles tradition to a greater or lesser degree, and chandlers that serve the canal trade often stock painted canalware like mugs, creamers, spoons and the ever-present Buckby Can.

I suspect no one reading this will be surprised to learn that Roses and Castles is not exactly the aesthetic I’ve been trying to achieve on the “Lucky Nickel”. It’s clean and tidy and modern, and I like it that way. Then again, if you were fortunate enough to be invited on board you might glimpse one or two nods to the old traditions tucked away.

And now back to the “Lucky Nickel” and the question of how to properly adorn the boat with its proud new name. Even if I was to order the vinyl sticker I’d still have needed to pay a graphic designer to do a proper high resolution cartoon of the nickel image, and that was going to add to the cost of the vinyl option. Then I happened to pick up a business card for a London-based sign writer who specialised in narrowboats and decided to check out her website.

Hannah’s gallery features some traditional styles of narrowboat decoration of course, but it also shows a large variety of modern fonts and styles that I thought looked really smart, so I got in touch to ask about prices. Of course anything done bespoke and by hand is going to be more expensive than something spit out of a large format printer, but I was actually surprised that the costs were reasonable. Sure it was more than the graphic artist + vinyl sticker option, but not crazy more. And it promised to be a much nicer job. I’m not against new methods. I've got solar panels and LED lighting and streaming Netflix, so this is a thoroughly modern boat. But getting this done properly, by hand, somehow just felt right.

Many emails were exchanged that eventually resulted in the lovely Hannah arriving on Monday morning with a small backpack containing the tools of her trade. We’d already agreed on the design, and she’d hand drawn a new image of the nickel that was absolutely perfect. She then had the whole layout printed in full scale so we could spend a bit of time faffing around positioning the printout on the side of the boat, debating whether it should be half an inch higher or lower, until I finally agreed and disappeared to let her get on with it.

The process itself was interesting. She used a piece of carbon paper sort of stuff and a straight edge and a steady hand to press through the printout and transfer the outline onto the side of the boat. After that, she simply sat on the towpath with her tiny pots of paint and her even tinier brushes and meticulously filled in the whole thing. And she never even went over the lines! It took a bit more than two days, with a short break on Day Two for me to fire up the boat and turn it around so she could do the other side.

The end result is fantastic. I’d originally thought the lettering should curve around the nickel, but this layout was one of Hannah’s suggestions and it’s much much better. Astoundingly astute Go Stay Work Play Readers may recognise that font as a knock-off of the one used on all Transport for London signage. It’s the tube font!

The question then became one of how to get the new name properly displayed on the boat. I’ve been on the canals full time for more than two months now I’m a little surprised at how many boats I see with no name visible at all. I find this odd and a bit sad. I suppose different boatowners have different priorities but honestly, have some pride, people! For a long time I’d planned to simply have a custom vinyl sticker created from an online company like this one. It seemed like a reasonably economical way of achieving the effect I was looking for, and they even promised they could take a digital image file of the nickel and create a sticker of that, along with the lettering. Job done, I thought.

First, though, let’s have a little sidebar and delve into the rich and colourful history surrounding the painting and decoration of narrowboats. And when I say “colourful history” I am definitely not speaking metaphorically. Traditionally, working narrowboats operated and inhabited by bargemen and their families were be heavily decorated in what’s come to be known as the “Roses and Castles” style, which AGSWPLRs might suspect runs heavily to… er… roses and castles. And of course they’d be right.

I told you it was colourful.

"Their response to this situation seemed to be to develop an even stronger trade mystique, to brazen out the common perception with a display to confound their critics. These 'dirty bargees' turned their boats into models of ostentatious cleanliness with polished brasswork and woodwork scrubbed to snowy whiteness, and their squalid little box cabins were transformed into domestic palaces of lace edged curtains and china plates. If they could not impress with quantity on their tiny floating homes they would dazzle with quality, and every surface was painted, every moulding picked out with strong colour, and every tin utensil smothered in painted roses and romantic landscapes.”

(From Canal Junction)

One can certainly imagine that it might be nice to be surrounded with such colourful and romantic images given that life on a working boat was hardly a bed of roses.

Or even a bed of castles, for that matter.

Or even a bed of castles, for that matter.

Before the modern era of us pampered boat dwellers with our giant below-decks water tanks and hot water heaters and such-like, clean water was stored in a metal tin called a Bucky Can, normally stored on the roof of the boat and refilled at infrequently located towpath standpipes. (Actually, the infrequently located towpath standpipes are still the only source of clean water…) Just as with everything that wasn’t nailed down (and many things that were) Bucky Cans were also heavily decorated.

The "Lucky Nickel" collection of canalware

Hannah’s gallery features some traditional styles of narrowboat decoration of course, but it also shows a large variety of modern fonts and styles that I thought looked really smart, so I got in touch to ask about prices. Of course anything done bespoke and by hand is going to be more expensive than something spit out of a large format printer, but I was actually surprised that the costs were reasonable. Sure it was more than the graphic artist + vinyl sticker option, but not crazy more. And it promised to be a much nicer job. I’m not against new methods. I've got solar panels and LED lighting and streaming Netflix, so this is a thoroughly modern boat. But getting this done properly, by hand, somehow just felt right.

Many emails were exchanged that eventually resulted in the lovely Hannah arriving on Monday morning with a small backpack containing the tools of her trade. We’d already agreed on the design, and she’d hand drawn a new image of the nickel that was absolutely perfect. She then had the whole layout printed in full scale so we could spend a bit of time faffing around positioning the printout on the side of the boat, debating whether it should be half an inch higher or lower, until I finally agreed and disappeared to let her get on with it.

The paper layout in position.

Hard at work. At least it was sunny the first day.

This is NOT photoshopped! This is just pure, un-re-touched, hand painted awesomeness. I can’t tell you how excited this makes me. It’s like the boat is finally properly reborn.

And I couldn't resist this bit of fun. After all, I did say I was using the tube font!

And this is definitely not a gap you want to ignore!

Me and my colour coordinated boat. Happy happy.